Outlook • December 3, 2025

Awash in Wine: Insights on the Inventory Glut

Winescape Winter 2025/2026 | Trending Topic

Report Snapshot

Situation

Many wineries have more wine in bottles, tanks and barrels than they can reasonably expect to sell in a timely manner at profitable prices. My calculations suggest that wineries had nearly 30% more inventory than the market should ideally carry at midyear 2025. The root cause of this inventory glut is a decline in wine consumption that began in 2022.

Finding

To help determine how quickly the inventory imbalance could be corrected, I’ve produced ballpark estimates of the size of the inventory overhang as well as projections for what the situation might look like heading into the 2026 harvest under various scenarios.

Outlook

Underproduction will eventually bring inventories back in line. Under my base-case scenario, the small California grape harvest in 2025 will go a long way toward reducing the inventory overhang, which should in turn help firm up grape demand in 2026.

My calculations suggest that wineries had nearly 30% more inventory than the market should ideally carry at midyear 2025.

Many wineries are struggling under the weight of unneeded inventory, which is in turn depressing grape demand. This article examines the nation's inventory glut and outlines how quickly it might be resolved.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a straightforward task due to imperfect data, uncertainty surrounding the size of the 2025 California grape harvest, and questions around the trajectory of wine sales. With this in mind, I’ve produced ballpark estimates of the size of the inventory overhang as well as projections for what the situation might look like heading into the 2026 harvest under various scenarios.

The inventory glut is quite large. My calculations suggest that wineries had nearly 30% more inventory than the market should ideally carry at midyear 2025. Under my base-case scenario, the small California grape harvest in 2025 will go a long way toward reducing the inventory overhang, which should in turn help firm up grape demand in 2026.

A wide range of outcomes are possible. Thus, wineries and growers should continue to closely monitor the market data, as the status of the inventory glut should become clearer by spring.

The Inventory Glut

Maintaining the appropriate amount of inventory is always a delicate balancing act for wineries. They must hold more inventory than producers of most other products because wine generally requires aging before it is released for sale. For high-end red wines, this is generally three years or more.

The root cause of the current inventory glut is a decline in wine consumption that began in 2022.

Given the uncertainty of where sales will be that far down the road, it is always a challenge for wineries to maintain a balanced inventory position. This is made more difficult by the normal variation in grape output from year to year and long lead times to produce new grapes.

Today, many wineries have more wine in bottles, tanks and barrels than they can reasonably expect to sell in a timely manner at profitable prices.

The root cause of the current inventory glut is a decline in wine consumption that began in 2022. Wineries were slow to adjust production when the market turned and have produced more than they’ve sold in recent years. Some grape growers also made wine from unsold grapes, hoping to sell the bulk wine to wineries later, adding to the current inventory glut.

The inventory glut is problematic for wineries, grape growers and the industry more broadly. Specifically:

- Inventory is costly to hold. The resources locked up in unneeded inventory can’t easily be tapped to fund current expenses, new production or future expansion.

- Excess inventory exerts downward pressure on wine prices, as producers who are long may resort to discounting to stimulate sales.

- Because wineries are now compensating for past overproduction by underproducing, they needed fewer grapes from the 2025 crop than they would have if inventories were in balance. For growers, this sapped grape sales.

Underproduction will eventually bring inventories back in line. However, this has drawbacks, as vintners prefer to release new vintages on a regular schedule so that they have fresh products to sell to consumers. It generally isn’t feasible for wineries, particularly those competing at the high end of the market, to drastically reduce production or skip a vintage entirely, as it may prove detrimental to future wine sales.

While reductions in production will be the main solution to the inventory glut, there are other means to reduce excess inventory as well. Discounting wine to temporarily stimulate sales will likely continue to occur until the inventory overhang is absorbed. However, this must be approached with caution, as it can destroy brand value. Some excess wine may also eventually be disposed of or transitioned to lower-value uses such as distilling material or cooking wine.

Past inventory gluts were easier to resolve because wine sales were growing. Because sales are now declining, the correction will prove to be more challenging.

How Large Is the Inventory Overhang?

To appreciate how long it might take to resolve the inventory glut, it is first necessary to estimate its size.

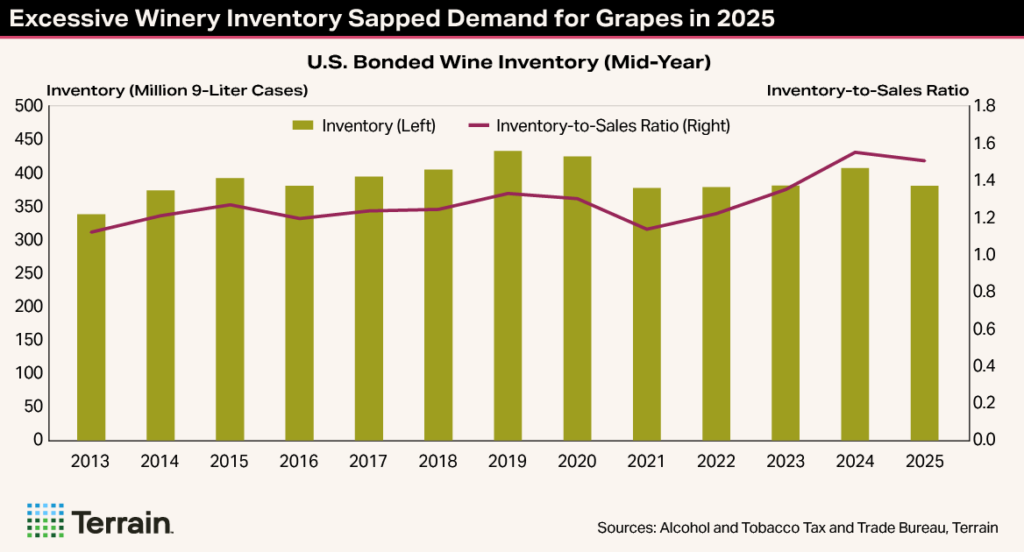

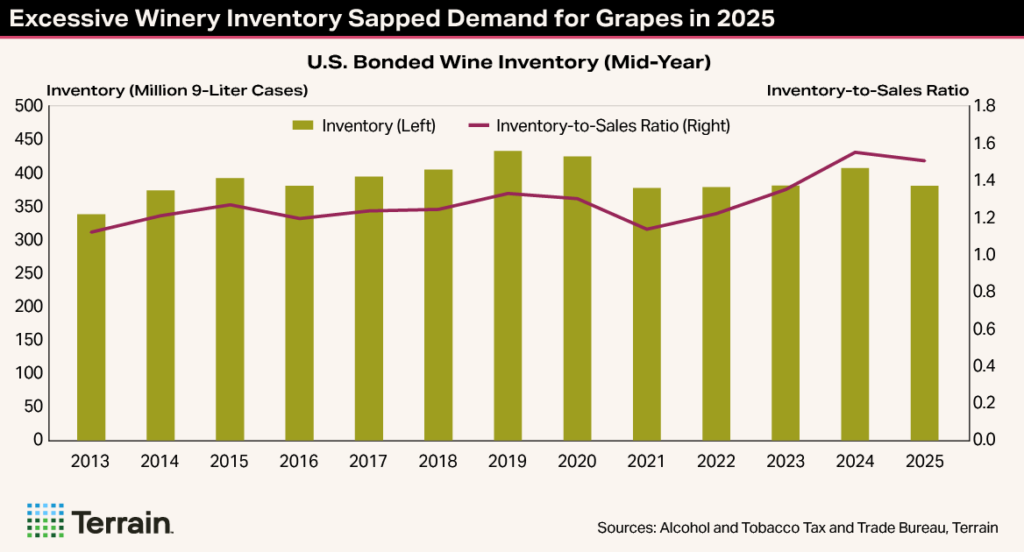

The chart illustrating excess wine inventory shows bonded wine stocks held by U.S. wineries, including both finished (bottled) and unfinished (bulk) wine, as of June 30 each year, as well as the inventory-to-sales ratio over the prior 12 months.

Note that the math doesn’t always add up, and it is possible that wine inventory has been overstated in recent years. Despite the anomalies, the data should provide a reasonably close approximation.

Based on the data from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), wineries held approximately 380,000 cases of wine in absolute terms heading into the 2025 harvest, which is slightly below the historical average. However, the inventory-to-sales ratio is the more relevant metric. It measures how long it would take to sell through current inventory at the current pace of sales, providing a better gauge of whether inventories are long or short.

The ideal inventory-to-sales ratio today is lower than it was in the past because wine sales are declining.

The current inventory-to-sales ratio stands at about 1.5, equivalent to just over 18 months of supply based on past 12-month sales. This compares with an average of less than 1.25 (14.8 months) from 2014 to 2018, a period when inventories were thought to be roughly in balance. Thus, inventories are clearly high relative to historical levels.

The current ideal inventory level is 298 million cases.

The ideal level of inventory depends on the trajectory of wine sales. When wine sales are growing, wineries need to hold more inventory to satisfy future demand than when sales are shrinking. Thus, the ideal inventory-to-sales ratio today is lower than it was in the past because wine sales are declining. We are holding excess inventory.

This compares with actual inventory of 382 million cases.

Using the 2014 to 2018 average ratio as a baseline (when inventory was relatively balanced), I adjust down based on the assumption that wineries expect sales to decline at a 3% annual rate going forward. This yields an ideal inventory-to-sales ratio of 1.18 (14.15 months). Based on this figure, the current ideal inventory level is 298 million cases.

The current excess inventory is enough extra wine to fill 10,400 standard-size swimming pools.

This compares with actual inventory of 382 million cases, which implies there are 84 million cases of excess inventory. I want to emphasize this is a “ballpark” estimate because the underlying data are imperfect.

The current excess inventory is enough extra wine to fill 10,400 standard-size swimming pools. We are, indeed, awash in wine.

To bring this home to grape growers, the nation’s inventory overhang is equivalent to 1.2 million tons of grapes, assuming a ton of grapes produces 165 gallons of finished wine.

The TTB data do not detail the composition of the inventory overhang. Some appellations, varieties and quality tiers are inevitably in a more balanced position than others.

The Short California Harvest Will Help

Underproduction in 2025 will almost certainly help reduce the inventory overhang. Most market experts believe that less than 2.5 million tons of California grapes were crushed in 2025, and perhaps substantially less. My own estimate of 2.4 million tons is below the 2.9 million tons crushed last year and an average of more than 4 million during the mid-2010s peak.

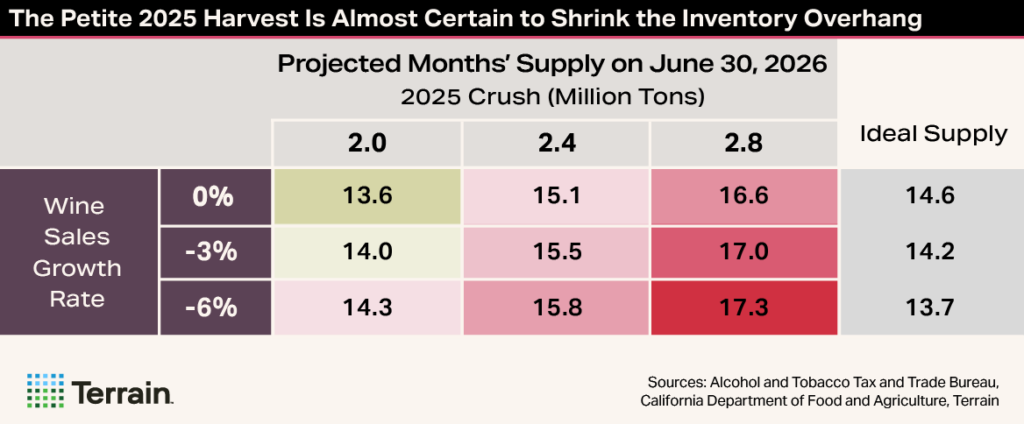

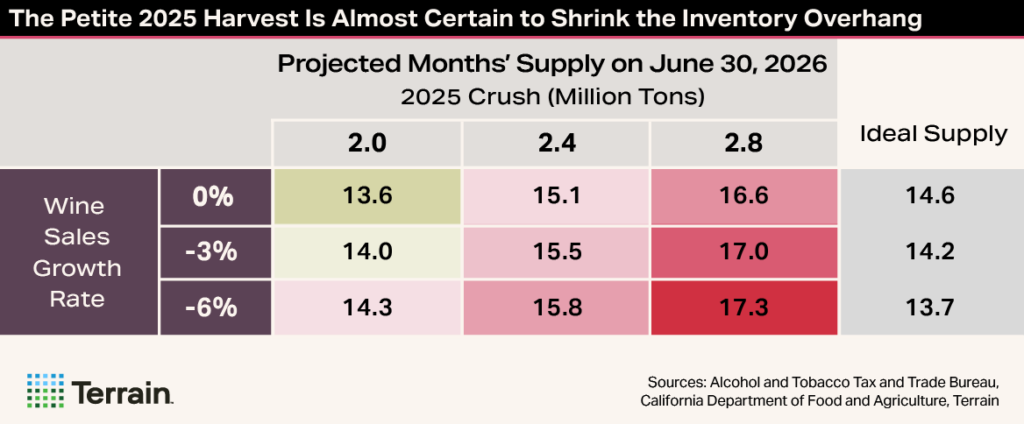

The magnitude of the inventory reduction will depend on how many grapes were crushed and the trajectory of wine sales. To shed some light, I’ve produced projections of the inventory imbalance at midyear 2026 based on various scenarios for these two variables. (This exercise should be considered illustrative rather than definitive due to imperfect data.)

Based on tax data from the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, I believe that approximately 222.5 million cases of wine made from California grapes were shipped to market in the 12 months ending in June. Assuming the inventory of California wine is proportional to its share of national wine shipments, I estimate there were approximately 74 million case equivalents of excess California wine heading into the 2025 harvest.

This represents 18.1 months of supply, the same as the national figure because I assume the inventory-to-sales ratio is the same. It also equates to just over 1 million tons of grapes, or around 40% of what is expected to have been crushed in 2025.

The table shows my projections of the months’ supply at midyear 2026, based on various assumptions pertaining to the size of the 2025 crush and wine shipment growth. The ideal inventory varies based on the wine sales growth assumptions. These are shown in the final column of the table to facilitate comparison.

Under my base-case assumption (2.4 million tons crushed and -3% sales growth), we would have 15.5 months of supply, versus a target figure of 14.2 months. Still long but much better than the inventory-to-sales ratio heading into the 2025 harvest.

Under the most optimistic scenario (2 million tons and flat sales), wineries would be slightly short on inventory. Under the most pessimistic scenario (2.8 million tons and -6% growth) the reduction would be minimal, and we would still be severely long in inventory prior to the beginning of harvest next year.

Again, these are ballpark estimates and they pertain to aggregate inventory levels. Shortages or surpluses for specific appellations, varieties and quality tiers are possible under any of these scenarios.

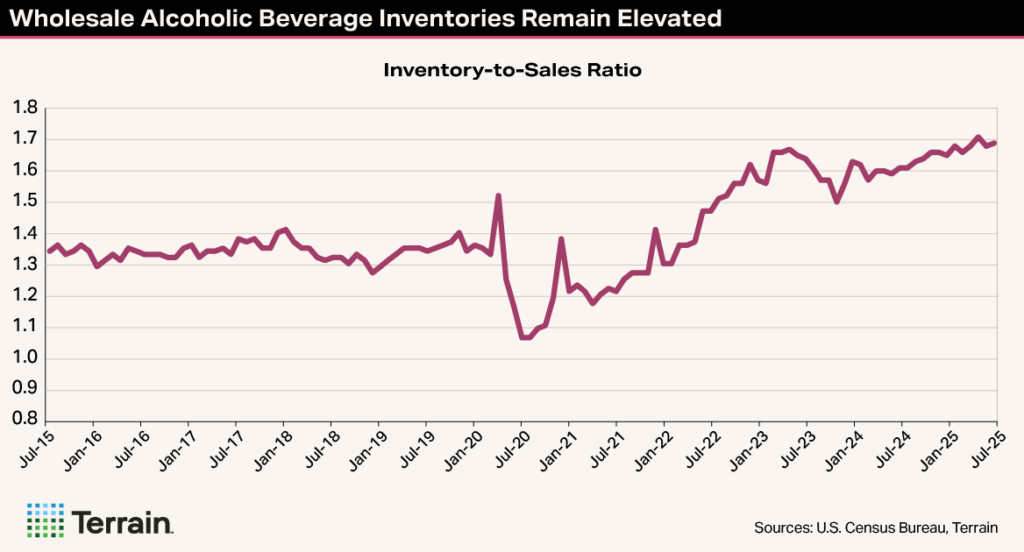

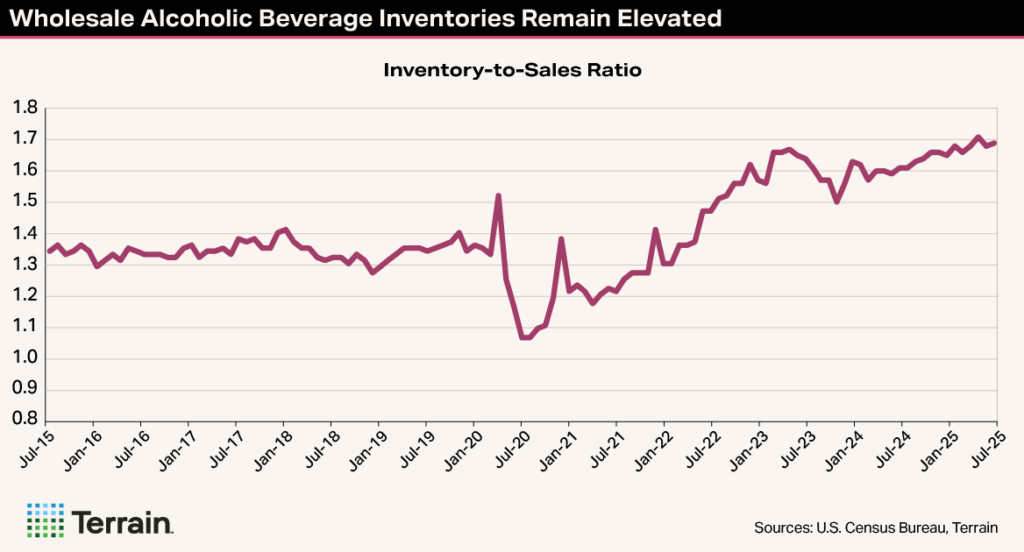

The analysis does not consider that excess wine inventory could potentially be transitioned to alternative uses or that wholesalers and retailers may be long on inventory as well. While retailers have pared inventories substantially based on the differential between depletions and retail sales in recent years, wholesale alcoholic beverage inventories are still elevated in dollar terms. Although, we don’t know how much of the excess here is wine.

The crux of the matter is there is still a lot of uncertainty on the inventory front. Inventories will likely be closer to balance next year, though the range of potential outcomes is wide.

Implications for Grape Demand

The potential reduction in inventory has positive implications for grape demand. Wineries will need to crush more grapes in 2026 than they are expected to have crushed in 2025 in all but the most pessimistic scenarios.

Under my base-case scenario, California wineries would need to crush just over 3 million tons in 2026 if they began in a balanced inventory position. However, because they would still be modestly long, the ideal crush (that required to bring inventory back into balance) would be around 2.7 million tons. Under the most optimistic scenarios, demand could be 3 million tons or more.

We may well have hit bottom in 2025, as the grape market is likely to be closer to balance under all but the most pessimistic scenarios.

Note that these represent “ideal” inventory scenarios — the quantity of grapes that producers would need to support expected future sales and achieve and maintain a balanced inventory position. It is possible wineries could continue to underproduce and take fewer grapes than this out of an abundance of caution or because of cash flow issues. (Although, underproduction could be detrimental to future sales.) And under the most pessimistic scenarios, grape sales may not improve at all next year.

What is certain is that there will be less capacity to produce grapes next year, and hence competition, as vines continue to be removed. Thus, we may well have hit bottom in 2025, as the grape market is likely to be closer to balance under all but the most pessimistic scenarios. Nonetheless, wineries may still be hesitant to pay higher prices if consumers continue to push back on bottle price increases.

It is not outside the realm of possibility that a grape shortage could materialize next year, as California growers may not be capable of producing 3 million tons due to vineyard removals, mothballing and abandonments. And there is less margin for error now in the event of any major disruption in yields.

Final Takeaways

The small 2025 California grape harvest should go a long way toward reducing the inventory glut. This in turn should help firm up demand for grapes in 2026.

However, the magnitude of the inventory reduction will depend on just how small the 2025 crush turns out to have been, as well as the trajectory of wine sales. Both are uncertain, so a wide range of outcomes are possible.

Given this, wineries and growers will need to be flexible and should continue to monitor the market closely, as it could turn quickly. Unfortunately, we may not have firm figures on the size of the 2025 crush or post-crush wine inventory until March, so there will be an element of blind negotiations in the first stages of the year.

I would advise wineries that are confident in their sales forecasts and know they will need grapes not to hold out too long. There are likely to be fewer opportunities as the 2026 harvest season approaches than there are today.

Tough decisions lie ahead for growers with uncontracted fruit. For those that have desirable varieties and the ability to produce quality fruit at a reasonable price, my advice is to continue to farm at least minimally until there is more clarity in the market.

For those with unproductive vines in marginal areas or where there are viable alternative uses, it may be wise to consider alternatives. Because supply and demand dynamics vary widely across appellations, varieties and quality tiers, I also recommend seeking expert advice if the decision isn’t clear cut.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.