Report Snapshot

Situation

Now that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) is signed into law, the 45Z Clean Fuel Production tax credit will remain in place through December 31, 2029. Plus, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has proposed the largest Renewable Volume Obligations (RVOs) to date. However, key issues remain unresolved, including treatment of Small Refinery Exemptions (SREs), the greenhouse gas (GHG) model to be used to determine Carbon Intensity (CI) scores, and verification of Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices.

Outlook

The OBBBA and newly proposed RVOs signal strong federal support for domestic biofuel production in the next few years.

Finding

Changes to the GHG calculation for 2026-2027 may help ethanol plants qualify for credits and pass along benefits to farmers.

Impact

Farmers interested in producing low-CI grain and oilseeds should document CSA practices to verify eligibility once the Department of the Treasury and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) finalize guidance. Proactive discussions with local processors are essential, as biofuel producers, not farmers, claim 45Z credits.

Introduction: Fields to Fuel

The OBBBA signals a commitment to domestically sourced biofuels and feedstocks by unbundling CSA practices; removing the Indirect Land Use Change penalty, i.e., land use changes associated with biofuels production such as the conversion of wetlands or forestlands into crop production; and prioritizing North American feedstocks under 45Z. Combined with robust RVO prospects, increased consumption of home-grown grain and oilseed commodities could lead to premium pricing for farmers. Grain and oilseed farmers should work with local biodiesel and ethanol processors before adopting CSA practices to confirm 45Z tax credit sharing.

Biofuel Backstory

Before the OBBBA, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 promoted domestic biofuel production through two key tax credits:

- The 40A Biodiesel Blenders Tax Credit offered $1 per gallon for biodiesel and renewable diesel blenders and applied to domestic and imported fuels.

- The 40B SAF tax credit ranged from $1.25 to $1.75 per gallon for SAF sold in 2023–2024, requiring at least a 50% reduction in GHG emissions compared to conventional jet fuel.

To qualify, SAF (40B) required bundled grain and oilseed CSA practices—such as cover cropping, reduced tillage, and enhanced-efficiency nitrogen application (corn only).1 The bundling requirement significantly limited the number of corn and soybean acres eligible for a CI reduction.

Unbundling the CSA practices would increase significantly the amount of corn and soybeans produced with lower CI scores.2

In January 2025, the Biden administration issued guidance that merged 40A and 40B into 45Z for 2025–2027, and tied 45Z to unbundled CSA practices.3 The tax credit also applies to biofuels such as low carbon ethanol, in addition to biodiesel, renewable diesel and SAF.4

The Treasury and IRS are responsible for defining the details of the credit, the GHG modeling used, and CSA practices that can lower carbon emissions.5 However, this was only guidance and the industry still awaits final regulations.

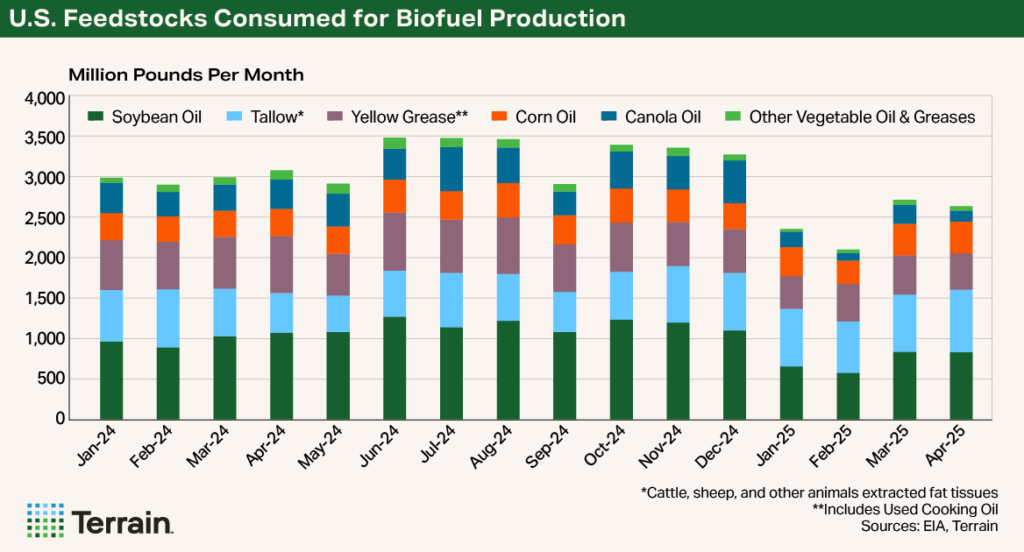

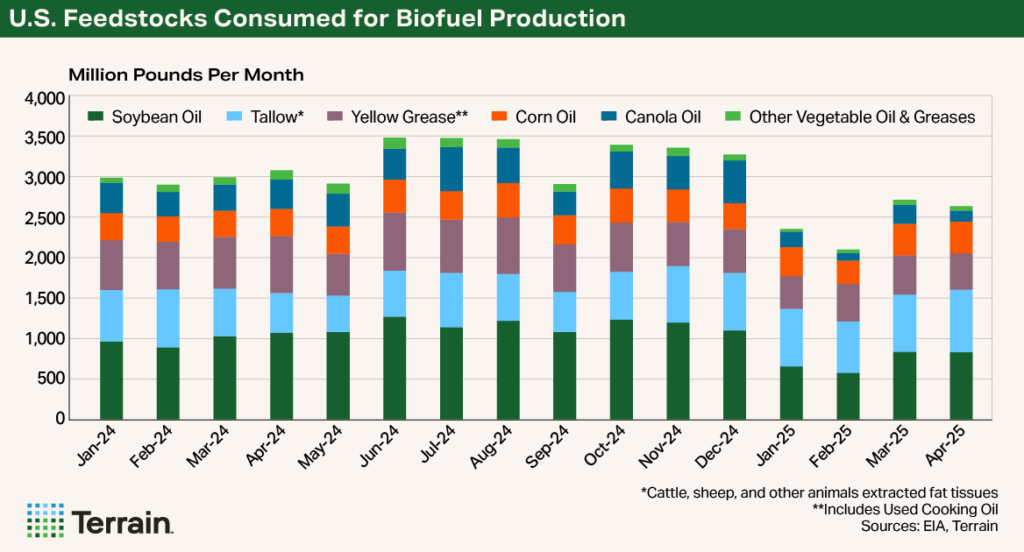

In the interim, biofuel plants have been idled or running at a reduced capacity given the uncertainty.6 Due to the lack of clarity, feedstocks consumed for biofuel production were also reduced at the start of 2025, down the first four months nearly 30% compared to the same time last year. Now that the industry has some clarity, feedstocks consumed for biofuel production should ramp up going forward.

With the passage of the OBBBA and the unbundling of CSA practices, more farmers—and the biofuel producers who purchase their grain and oilseeds—can achieve lower CI scores, increasing eligibility for 45Z.

OBBBA provided additional clarity on the 45Z tax credit by extending the credit period to December 31, 2029, and redefining qualified feedstocks.7 While the retention of 45Z and the extension offer more certainty, biofuel stakeholders still seek longer-term commitments beyond four years to support continued investment in the industry. With 45Z and OBBBA in place, attention now turns to how farmers can benefit from the evolving low-carbon biofuel landscape.

From Dirt to Data: Making Low-CI Farming Pay

With the passage of the OBBBA and the unbundling of CSA practices, more farmers—and the biofuel producers who purchase their grain and oilseeds—can achieve lower CI scores, increasing eligibility for 45Z. To support this, Iowa State University Extension developed a customizable tool that helps farmers estimate their CI score, project changes from adopting CSA practices, and calculate the potential tax credit value to ethanol plants. While USDA also has a CI calculator, the Iowa State tool helps quantify the practice in a tax credit dollar amount.

Farmers participating in USDA’s CSA pilot program cannot stack credits from voluntary carbon offset or inset markets, though they may still enroll in conservation programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) or the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP).8 With OBBBA, USDA will need to finalize the pilot program and the CSA practices involved to lower CI scores of grain and oilseed production.

Accurate recordkeeping is essential, as each CSA practice must be certified. Although biofuel producers file for the tax credit, the IRS has not finalized whether farmers will utilize the “Book and Claim” or “Mass Balance” method to verify CSA grain and oilseed feedstocks. In a “Book and Claim” model farmers would have certificates not assigned to specific grains produced that would allow ethanol plants to purchase the certificates. In a “Mass Balance” model the low-CI attribute would physically move with the bushel of grain or oilseed until sold to a co-op or ethanol facility. Both are hypothetical concepts with no current indicators as to how this would be implemented in the biofuel market, and if third party verification is required this will be an additional expense. Ultimately this is another pending IRS decision on how the credits will be managed and tracked.

Small Biodiesel Tax Credit & Transferability

Additional beneficial provisions supporting farmers in the OBBBA include reinstatement of the Small Agri-Biodiesel Producer Tax Credit at $0.20/gallon—up to 15 million gallons—for biodiesel producers using soybean oil. Previously $0.10/gallon, this credit expired in 2024 and can now be stacked with the 45Z tax credit, encouraging soybean oil feedstock use.

Farmers located near biodiesel plants may benefit by producing low-CI oilseeds and negotiating shared credit arrangements with small biodiesel producers in their geographic area. OBBBA also confirms that 45Z credits are transferable, allowing producers, especially farmer-owned or cooperative ethanol plants without federal tax liability, to sell credits on the secondary market, expanding flexibility to access credit benefits.

North America First: The Feedstock Shift

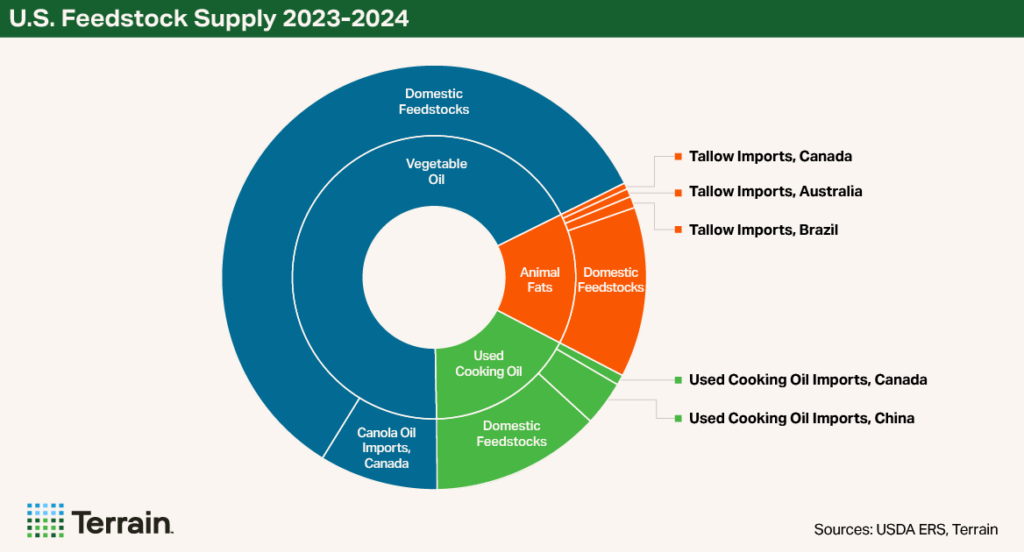

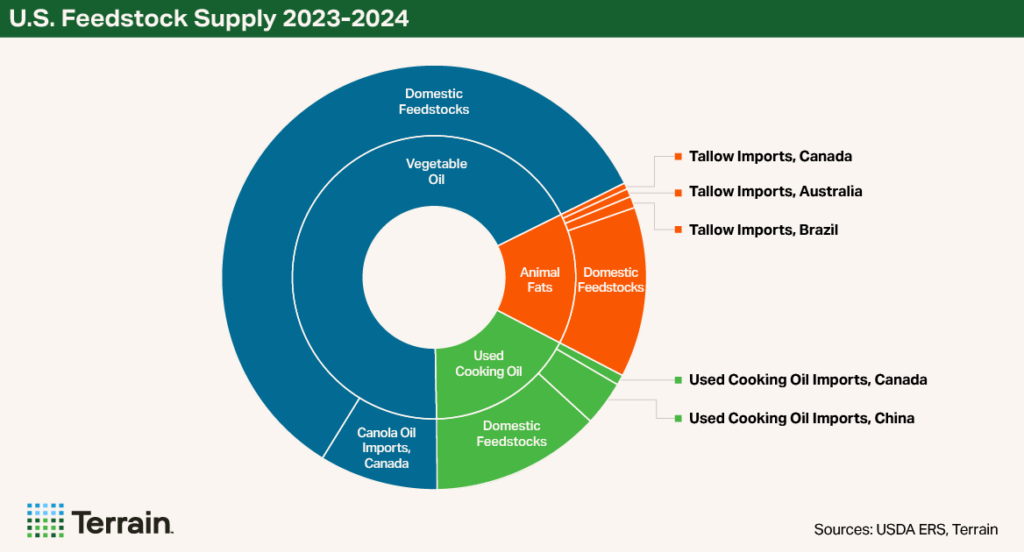

Additionally, the OBBBA introduces a strategic pivot in feedstock sourcing and redefines the competitive dynamics of the global biofuel supply chain. Starting in 2026, only North American-produced feedstocks such as soybean oil, canola oil, corn oil, tallow, yellow grease, etc., will qualify for the new tax provision, meaning imported substitutes like used cooking oil (UCO) from China, imported tallow, and sugar cane-based ethanol from Brazil** will no longer qualify for the 45Z tax credit. The policy change will favor soybean oil, canola oil and corn oil from processors in North America and should provide support for higher grain and oilseed processing pace. Prices for North American feedstocks like soybean oil, canola oil, corn oil, UCO and tallow will likely increase. Soybean oil prices have risen over 20% since mid-June to the end of July 2025, although they are still well below the record high prices of April 2022.9 We could also see a ramp up in biofuel production for the remainder of 2025 as foreign feed stocks still apply for the 45Z tax credits in 2025.

45Z Cuts ILUC from the GHG Equation

Complementing the shift toward domestic feedstocks, the OBBBA redefines how emissions are calculated—most notably by removing the controversial Indirect Land Use Change (ILUC) factor from the 45Z lifecycle GHG equation, which previously meant land-based feedstocks like grain and oilseed commodities did not qualify for 45Z. By excluding the ILUC,* every CI score for grain and oilseeds produced here in the U.S. will now be lower in 2026-2029, although it is still included in the calculation for 2025. The ILUC is still used in the GHG emissions lifecycle for the RFS for corn-based ethanol production, so there are inconsistencies in two federal programs (45Z tax credit and RFS minimum biofuel obligations) on how ILUC is factored in CI scores.

Suppose the RFS adopts the 45Z logic and removes ILUC from GHG/CI calculators. In that case, this should improve corn-based ethanol CI scores, giving ethanol producers a higher tax credit per gallon, potentially increasing ethanol production and thus more domestic consumption for corn.

Since the ILUC has been excluded from the GHG calculation, producers should see how this improves their CI score of grain and oilseed commodities and corresponding credit values, and they should discuss with local biofuel producers how the 45Z tax credit will be shared.

SAF’s Descent: Grounded by 45Z?

While removing the ILUC penalty improves prospects for land-based feedstocks, SAF faces new challenges under the revised 45Z tax credit framework. Previously eligible for up to $1.75/gallon tax credit, SAF now receives the same $1/gallon tax credit as other biofuels.10 SAF must still demonstrate a 50% reduction in GHG emissions. Still, SAF production is more complex and costly, requiring about two gallons of ethanol to produce one gallon of SAF from the alcohol-to-jet process.11 Under 45Z, credits cannot be stacked when multiple fuels are derived from the same feedstock, further limiting SAF’s appeal.

These constraints, along with rising costs and limited long-term federal support, have led many airlines12 and refiners to pause SAF investments.13 The Hydro-processed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA) process14 can produce SAF or renewable diesel. Most refiners have been prioritizing renewable diesel production (which is more profitable), with production doubling over the past two years. Given the revised and equivalent tax credit value, this trend is likely to continue.

Even with the previous $1.75 tax credit, alcohol-to-jet SAF costs $1.24 per gallon more than fossil jet fuel; with the $0.75 reduction in the credit in 2026, the gap will widen to $1.99.15 While some states*** offer stackable incentives (both the federal 45Z tax credit combined with a state tax credit), SAF adoption remains limited. Without stronger federal support or consumer willingness to pay more, SAF production is unlikely to scale soon given the cost disadvantage compared to conventional aviation fuel and renewable diesel.16

As SAF struggles to gain traction under the revised credit structure, other biofuels stand to benefit from regulatory tailwinds—particularly through expanded RVOs and more favorable RIN generation rules.

RINs and Wins

On June 13, 2025, just before the OBBBA was signed, the EPA proposed 2026–2027 RFS**** volumes that nearly doubled RVOs—from 3.35 billion gallons in 2025 to 5.61 billion in 2026 and 5.86 billion in 2027.17 If this proposal is implemented, it would be a significant win for the biofuel industry, which has long argued that prior RVOs were too low relative to domestic capacity and planned capacity, providing less market opportunity for biofuel producers, domestic processors and grain and oilseed farmers.

The proposal also favors domestic biofuel production from domestic feedstocks: U.S.-produced biofuels earn 100% of the RIN credit, while biofuel imports or U.S. production from foreign feedstocks earn only 50%. RIN values vary by fuel type—ethanol earns 1 RIN, biodiesel 1.5, and renewable diesel 1.6–1.7. For example, renewable diesel from imported used cooking oil earns just 0.8 RINs; in contrast, domestic soybean oil earns 1.6 RINs, boosting its value.18 This also means that although North American feedstocks like imports of Canadian canola oil will still qualify for the 45Z tax credit, biofuel produced from imported canola oil feedstock will only generate half the RINs of domestic feedstocks, further favoring U.S. soybean oil.

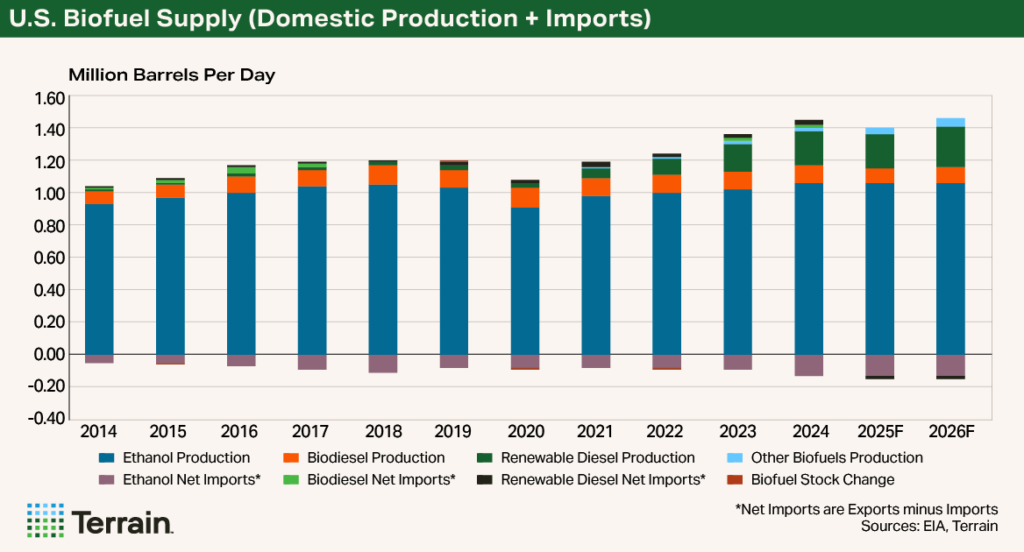

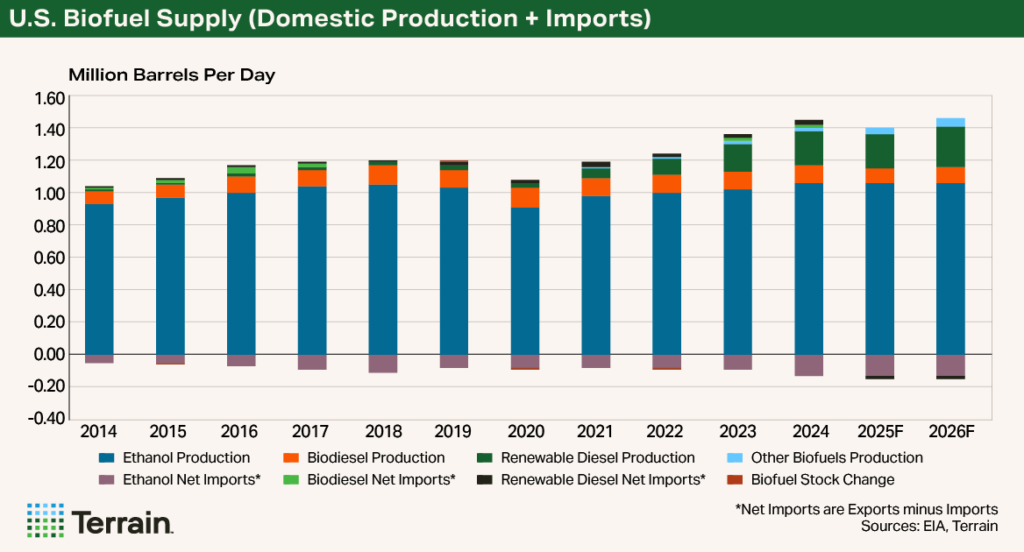

This shift is expected to increase soybean crush and reduce reliance on imports of feedstocks and biofuels as the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts for 2025 and 2026. A pivot toward liquid biofuels and RFS credits away from electric vehicles19 also benefits ethanol, biodiesel, and renewable diesel. But this is only a proposal, with the public comment period having ended August 8, 2025, and the final rule is not expected until later this year. The American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers have been in opposition of the proposal in its current format, so the final ruling could change direction between now and then.20

Waivers in Waiting: SRE Wildcard

While expanded RVOs and favorable RIN structures support biofuel growth, unresolved SREs remain a wildcard. SREs allow refineries (processing under 75,000 barrels/day) to petition for exemption from RFS obligations due to financial strain.21 These exemptions are applied retroactively, making it difficult to quantify their impact.22 If granted, they reduce the overall RVO for the year, as seen in 2017.

Currently, 189 SRE petitions from 2016–2025 await EPA decisions.23 If approved, they could reduce blending obligations and dampen feedstock demand. However, if denied, refiners must meet RVOs or purchase RINs, potentially increasing biofuel production.

There’s speculation that “Zombie RINs” (unused credits from prior years) could be used to clear the backlog without requiring meeting the original blending mandate.24 However, the proposed 2026–2027 RVO rule would require any SREs granted to be offset by other obligated parties. This change would stabilize demand and prevent future RVO reductions with SRE waivers. Biofuel stakeholders should monitor EPA developments on outstanding SREs closely as decisions could reshape future biofuel production and feedstock consumption.

45Z Credit Certainty & Crop Consumption

Despite lingering uncertainty around SREs and CSA practices and verification methods, the OBBBA has delivered long-awaited policy clarity for the biofuel industry. With 45Z tax credits secured for several years, producers and processors are expected to ramp up investment, production, and feedstock consumption. USDA’s 2025/26 forecast in the July World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) supports this momentum, with increased domestic soybean crush, reduced exports of soybeans and soybean oil, and higher soybean meal exports.25

Farmers interested in producing low-CI grain and oilseeds need to engage with local ethanol and crush plants to discuss how 45Z tax credits might be shared, as credit sharing is not mandated. Those selling to elevators or co-ops should initiate conversations before investing in CSA practices. While the OBBBA 45Z changes take effect in 2026, Treasury and IRS have yet to confirm which GHG calculator—GREET FD-CIC26 or USDA FD-CIC27 —will be used or how CSA data will be managed and documented by farmers, so those interested should start documenting now to be prepared when these announcements are finalized.

As policy clarity takes hold and the biofuel industry accelerates production, farmers who act early by knowing their CI scores; staying informed with Treasury, IRS, EPA and USDA final decisions; and collaborating with local grain and oilseed processors will be best positioned to capture value in this dynamic biofuel era. Farmers should negotiate with local biofuel producers on premium-priced low-CI grain and oilseeds and get in writing any agreement regarding the sharing of the 45Z tax credit prior to adopting any CSA practices and incurring these increased costs on their operations.

Appendix

*The original assumption of ILUC was that with increased global biofuel production, more global acres of land would expand into grain and oilseed production, therefore generating higher greenhouse gas emissions globally. The prior 45Z tax credit requirements were penalizing U.S. grain and oilseed farmers based on the assumption that South America would expand acres of grain and oilseed production purely for the support of biofuels.

**The reason Brazilian corn and sugar ethanol have lower CI scores versus U.S. corn ethanol is the assumption that the safrinha second-crop corn is double cropped following soybeans and, therefore, fewer inputs are needed (thus the lower GHG/lower CI score). For scope 2 emissions, U.S. ethanol uses natural gas and therefore has higher GHG/CI scores (mid-50s), while Brazil uses the sugar by-product bagasse to power their plants (with an average CI score between 40-47). The reason tallow imports have also surged (beyond just the favorable CI scoring) is because domestic production of tallow is limited due to flat growth in the livestock sector.

***California, Colorado, Iowa, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, Washington, Wisconsin.

****The RFS program was created under the Energy Policy Act of 2005 under the Clean Air Act. It was expanded in 2007 under the Energy Independence and Security Act to reduce dependence on imported oil and support domestic production of fuel alternatives. Under the RFS, oil refiners are required to blend biofuel into the conventional fuel supply or buy credits from those who do produce biofuel.28 Each gallon of ethanol or bio-based diesel is represented by a RIN, which is a credit that can be traded to measure compliance.29

Endnotes

23 https://soygrowers.com/news-releases/proposed-biofuel-blending-obligation-presents-an-opportunity-for-u-s-soy/

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.