Outlook • September 15, 2025

The Moderation Movement Part 2

Winescape Fall 2025 | Trending Topic

Report Snapshot

Situation

After more than two decades of growth, alcohol consumption appears to have peaked in 2021 and begun declining. In this follow-up piece to last issue’s Trending Topic on the demographic factors behind declining consumption, I focus on articulating the causes of the decline and whether it is likely to be temporary or a longer-lasting phenomenon.

Finding

The causes of the slump appear mainly structural, though economic pressures are likely playing a role as well. I see five plausible structural headwinds for alcohol consumption: demographic change, cannabis consumption, GLP-1 drugs, less in-person socializing, and changing attitudes toward alcohol and health.

Impact

The moderation movement has important repercussions for wine. Most importantly, wine will need to take market share in the alcohol category just to maintain its current volume of sales. Consumers are also apt to drink better wine if they drink less, and I expect a shift in preferences toward lighter wine styles and alternative packaging formats.

The Moderation Movement Part 2:

Why Americans Are Drinking Less

Following 2 1/2 decades of steady growth and a brief surge during the COVID-19 pandemic, alcohol consumption appears to have peaked in 2021. The National Institutes of Health indicates that consumption fell in 2022, and while more recent figures haven’t yet been released, other relevant data sources suggest that the decline has intensified since then.

The move toward moderation or abstinence is most evident among the younger generations (Gen Z and, to a lesser extent, millennials), as self-reported drinking rates for young adults have fallen sharply over the past decade. The decline in alcohol use has also been more pronounced for men than women and for non-Hispanic white people. I discussed these findings in detail in the first part of this two-piece series on alcohol consumption (Winescape | Summer 2025).

The moderation movement looks to be more than just a post-pandemic hangover.

In this piece, I focus on articulating the causes of the decline, which are varied, and whether it is likely to be temporary or a longer-lasting phenomenon.

The moderation movement looks to be more than just a post-pandemic hangover. Drinking did surge in 2020 and 2021, and the subsequent decline could initially be construed as normalization. However, consumption now looks to be tracking below its pre-pandemic level and there are no signs of stabilization as of midyear 2025. This suggests there are other factors involved.

The causes of the slump appear mainly structural, though economic pressures are likely playing a role as well.

I see five plausible structural headwinds for alcohol consumption:

- Demographic change

- Cannabis consumption

- GLP-1 drugs

- Less in-person socializing

- Changing attitudes toward alcohol and health

Wine will need to take market share in the alcohol category just to maintain its current volume of sales.

I don’t expect these headwinds to dissipate anytime soon. Thus, I project that consumption will continue to decline for the foreseeable future.

The moderation movement has important repercussions for wine. Most importantly, wine will need to take market share in the alcohol category just to maintain its current volume of sales.

Consumers are also apt to drink better wine if they drink less, and I expect a shift in preferences toward lighter wine styles and alternative packaging formats.

On an optimistic note, to the extent that declining alcohol consumption is being driven by health and wellness concerns, I believe that wine has some distinct advantages over other alcoholic beverages. But the industry needs to do a better job of explaining its virtues to consumers.

Are Economic Pressures to Blame?

Economic pressures may be contributing to the slump, but I don’t believe they are the main cause for two reasons:

- Alcohol consumption has been fairly resilient during past periods of economic distress. Consumers may trade down, but most drinkers continue to drink.

- Economic conditions haven’t been all that bad in recent years, though some financial stress is evident among lower-income consumers.

There have been three recessions since the turn of the 21st century. The shallow downturn in 2001 had almost no discernible impact on alcohol consumption.

In the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, the most severe downturn since the 1920s, per capita consumption declined just 2% despite acute financial distress, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. And consumption rose in 2020 when GDP dipped during the brief COVID-19 recession, though this period was atypical due to unprecedented government stimulus payments.

The U.S. economy has experienced an uninterrupted expansion since the COVID-19 recession ended in April 2020, and most consumers are still on relatively sound financial footing due to a strong labor market, rising real wages, surging stock prices and growing home values. The unemployment rate hasn’t exceeded 4.3% since 2021 and remains well below the 25-year average of 5.7%.

Nonetheless, consumers haven’t been feeling very optimistic. Sentiment has fluctuated near levels typically associated with recessions. Moreover, rising food, housing and healthcare costs, coupled with high interest rates, have caused financial strains for some, particularly those in the lower half of the income distribution. Consequently, auto loan and credit card delinquency rates have risen, though they are nowhere near Great Recession levels.

Financial pressures have likely caused some consumers to curb spending on discretionary items, including alcohol.

The younger generations, who are at the forefront of the moderation movement, have also faced some unique financial challenges, including rising student loan debt burdens and sky-high house prices. Even so, this narrative may be overstated, as a 2024 Federal Reserve study found that both Gen Z and millennials are doing materially better than their predecessors were at similar ages based on objective measures such as income and wealth.

Alcohol prices have also fallen 7% in real terms over the past five years, according to consumer price index data. So, affordability doesn’t appear to be the issue either.

Nonetheless, financial pressures have likely caused some consumers to curb spending on discretionary items, including alcohol. But I suspect the impact has been modest given that more severe periods of financial distress have had little effect on alcohol consumption in the past. Thus, there are almost certainly other factors involved as well.

Five Contributing Factors

I see five plausible structural factors that are likely depressing alcohol consumption. Only one represents a direct backlash against alcohol, while the others are side effects associated with broader social, demographic and technological trends.

1. Demographic Change

The U.S. population is both aging and becoming more diverse. This is a headwind for alcohol because consumption typically declines with age, particularly in the later stage of life, and multicultural consumers drink substantially less than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

While I can’t precisely quantify the differentials in alcohol consumption, I’ve produced ballpark estimates based on combining survey results relating to drinking frequency and intensity. The difference in per capita consumption between non-Hispanic white consumers and other racial ethnic groups looks to be in the range of 30% to 40%. And the drop in consumption as individuals age from their 60s to their 70s appears to be near 20%.

Declining consumption during the later stage of life is due to a combination of factors, including diminishing tolerance for alcohol, health-related issues such as medication interactions, and economic circumstances. The share of adults in their 70s began to increase quickly when the oldest boomers reached this threshold in 2016.

Increasing diversity is almost certainly part of the reason why the younger generations are drinking less.

The U.S. population has also become gradually more diverse, as each successive generation is more diverse than the preceding one. Lower alcohol consumption by non-white consumers is due partly to economic and cultural factors, though there is a biological basis as well. For example, many East Asians have heightened sensitivity to alcohol due to genetic differences that inhibit their ability to metabolize it.

The demographic transformation has been persistent yet very gradual, so it can’t explain the abrupt shift in alcohol consumption that began several years ago. Nonetheless, increasing diversity is almost certainly part of the reason why the younger generations are drinking less: Nearly three-quarters of boomers identify as non-Hispanic white, compared with just half of Gen Z, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Demographic change clearly represents a headwind for alcohol consumption, but a slow-moving one.

These demographic shifts will continue to progress gradually. The aging trend will accelerate over the next decade as the younger boomers reach their 70s, and one in five adults will be at least 70 by the early 2030s. The Census Bureau projects that non-white racial ethnic groups will account for all growth in the adult population in the coming decade and form 43% of the total in 2034, up from 39% in 2024.

Demographic change clearly represents a headwind for alcohol consumption, but a slow-moving one. Moreover, boomers are in better financial shape than their predecessors, so their consumption could potentially hold up better as they age. And alcohol use rates for white and non-white consumers have gradually narrowed over the past decade. If this continues, the impact of growing racial ethnic diversity could also be muted.

2. Cannabis

Like alcohol, THC, the main active ingredient in marijuana, is an intoxicant that facilitates relaxation and mood elevation. Historically, its use has been constrained by its status as an illegal substance. This began to change in 2012, when Colorado and Washington first legalized recreational cannabis. It is now “fully” legal in 24 states and the District of Columbia.

Consequently, marijuana use has surged. The 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicates that one in six adults used cannabis in the past 30 days — more than double the percentage in 2013. (This may overstate the actual increase, though, since users may have been more willing to self-report in the later survey given the growing social acceptance.)

And now, you can even drink your weed. Beverages infused with THC have skyrocketed in popularity in recent years, though sales still appear to be tiny in relation to alcohol. They are a closer substitute to alcohol due to their similar, drinkable method of delivery and ability to produce a buzz much more quickly than cannabis consumed in an edible form.

Low-dose versions derived from hemp, such as Cann and Wynk, are now being sold in some states where cannabis is illegal. This loophole was created by the 2018 farm bill, which federally legalized hemp-based products with low levels of THC. Moreover, these products can be found in supermarkets, convenience outlets, and liquor stores in some states, while traditional cannabis products can only be purchased in state-sanctioned dispensaries. Thus, they have the potential to reach a broader audience.

Has cannabis reduced alcohol consumption? The scientific evidence is still inconclusive. Some studies have found that cannabis can be a substitute for alcohol while others suggest they may be complements. Most of the studies are based on small and non-random samples, and I haven’t seen any that focus on drinks, so their results can’t be readily generalized.

However, there is clearly a substantial overlap between their audiences. The 2023 NSDUH found that 72% of past-month marijuana users also drank alcohol during the same month. Nearly one-quarter of past-month drinkers also reported using cannabis, up from 10% in 2011. From a financial standpoint alone, it seems probable that growing cannabis use is lowering alcohol spending.

There are also widespread anecdotal accounts of consumers substituting cannabis for alcohol. Reasons cited include perceptions that it is less harmful to health, has fewer calories, and delivers more “buzz” for the buck.

Cannabis likely has been stealing some occasions from alcohol, and this may be hastening because of the rise of THC drinks.

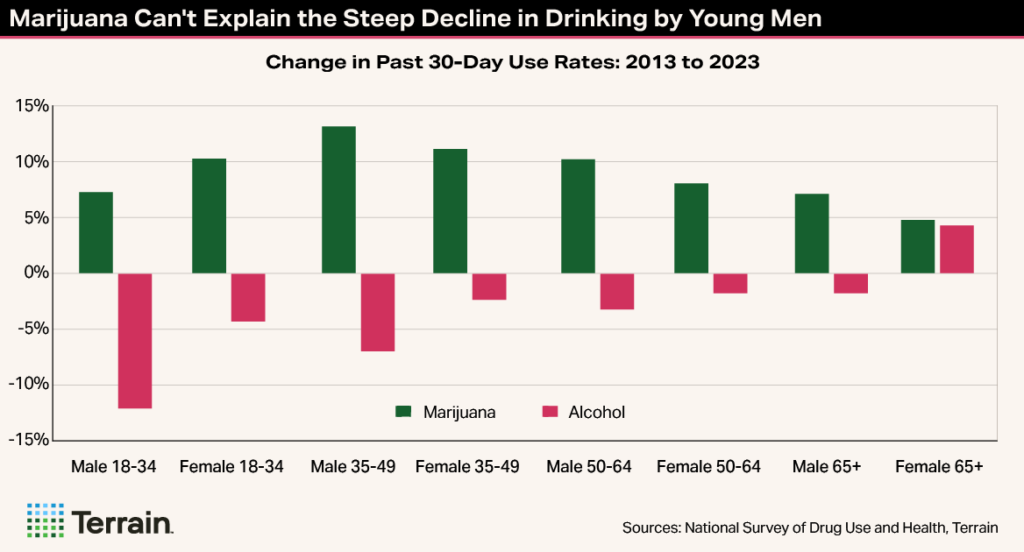

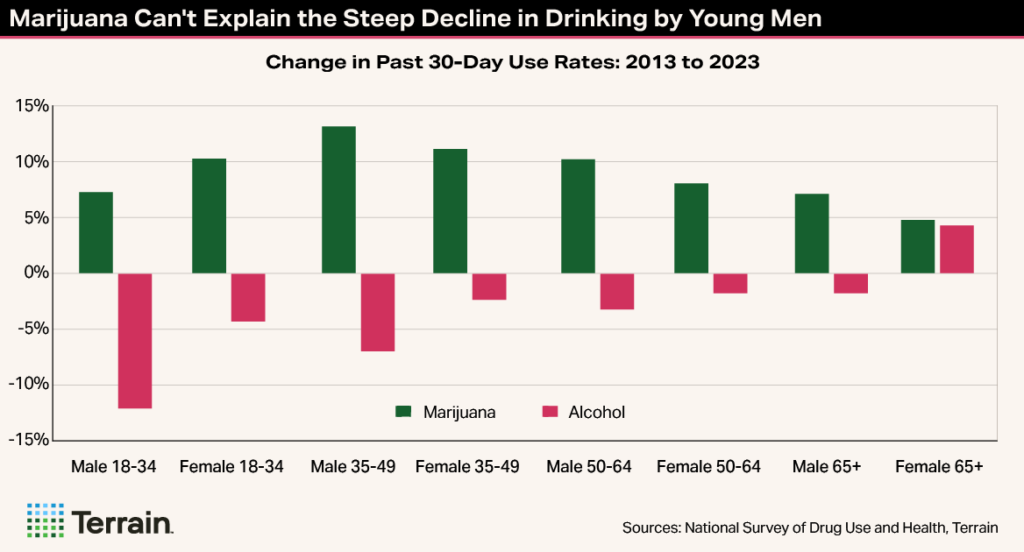

Even so, cannabis doesn’t appear to be the main explanation for why the younger generations are drinking less. While cannabis skews toward a younger audience, it always has. And the increase in use rates over the past decade has been greatest for 35- to 49-year-olds, yet their alcohol use hasn’t declined nearly as much.

Considering all the evidence, cannabis likely has been stealing some occasions from alcohol, and this may be hastening because of the rise of THC drinks.

The impact will almost certainly intensify as more states legalize cannabis. While national legalization does not appear imminent, the Trump administration is looking into reclassifying marijuana as a less dangerous drug, which is an important first step. Sales of THC drinks are also expected to continue to surge, though this is not a foregone conclusion given their murky legal status. For example, California banned hemp-based beverages in 2024, and more states are considering regulating or prohibiting them, including Texas.

3. GLP-1 Drugs

GLP-1 drugs (such as Ozempic, Mounjaro and Wegovy), which help to regulate blood sugar and suppress appetite, have become an increasingly popular treatment for diabetes and, more recently, weight loss. In addition to their intended effects, GLP-1s appear to have an important side effect: They reduce desire for alcohol.

GLP-1s were first approved for diabetes in 2005 and weight loss in 2014, though their use has been minimal until recently. Estimates of the percentage of adults taking GLP-1 drugs ranged from 6% to 10% in 2024.

Several recent survey-based studies found that GLP-1 use was associated with a statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption.

For example, a 2024 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that one in eight adults had tried them and 6% were currently using them. A Fairhealth study based on insurance claims data indicated that 4% of insured adult patients were prescribed a GLP-1 drug in 2024. This compares with less than 1% in 2020.

Are GLP-1 drugs suppressing alcohol consumption? Many users report drinking less because the drugs decrease the enjoyment of alcohol or promote feelings of fullness. And several recent survey-based studies found that GLP-1 use was associated with a statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption, though they don’t explicitly quantify the decrease.

The explosion in GLP-1 use in recent years also dovetails with the decline in alcohol consumption that began in 2022. Even so, they don’t look like the primary driver, as young adults, who are at the forefront of the moderation trend, have relatively low use rates. Conversely, GLP-1 use skews toward mature consumers, who have reported a smaller decline in alcohol use.

The impact of GLP-1 drugs is likely to intensify as their adoption increases, particularly for weight loss. Approximately half of American adults are thought to be eligible to take them, and a recent PwC survey found that 30% to 35% are interested in using them.

The main obstacle appears to be financial, as the “list price” of GLP-1 drugs often exceeds $1,000 a month. Insurance coverage, particularly in conjunction with weight loss, remains restrictive. It is difficult to predict how the insurance situation will unfold.

Nonetheless, competition among suppliers is growing, and some are beginning to offer lower prices to individuals lacking insurance coverage. Moreover, patents related to the active ingredient in GLP-1 drugs and their manufacture will expire over the next several years, paving the way for lower-cost generic versions. So, adoption is almost certain to surge in the years ahead, and GLP-1 drugs look to be a stiffening headwind for alcohol consumption.

4. Less In-Person Socializing

As a social lubricant, alcohol has long been a central part of the experience in many types of gatherings.

Leisure time spent socializing in person fell from an average of 5 hours per week in 2014 to 3.9 hours in 2022.

But Americans are spending progressively less time socializing in person, both in their personal and professional lives, and more time alone, with pets, and in digital spaces.

According to the American Time Use Survey, leisure time spent socializing in person fell from an average of 5 hours per week in 2014 to 3.9 hours in 2022, a decline of more than 20%, though it ticked back up to 4.1 in 2024. On the other hand, time spent on social media and in front of screens has risen sharply.

The rise of remote work has also reduced opportunities for in-person interaction in business-related settings. This means fewer meetings over meals and after-work happy hours where alcohol takes center stage. Convention center business remains below its pre-pandemic level.

Cell phones and social media also make it easier to capture and broadcast mischievous behavior, which can potentially have disastrous consequences. This may be causing some people to drink less or eschew alcoholic beverages entirely in social settings.

Are these societal shifts depressing alcohol consumption? I haven’t found any studies that address this topic explicitly, but it makes sense that less in-person socializing is reducing the number of potential drinking occasions. (Based on my personal experience, neither dogs nor Facebook are as good of drinking buddies as my friends, and I rarely imbibe during virtual business meetings.)

Moreover, the decline in socializing has been most pronounced for the younger generations. However, it began well before the recent U-turn in alcohol consumption, and consumption increased during the pandemic when there were strict prohibitions against in-person socializing. So, it doesn’t look like the primary driver.

Will this headwind persist? I don’t see a scenario in which screens and social media will occupy less of our leisure time going forward. Also, the younger generations, who are digital natives, will form an ever-larger share of the legal drinking age population with time. Conversely, the remote work trend does appear to be waning a bit. Some workers are returning to the office, though in many cases only on a part-time basis.

Thus, it is uncertain whether this headwind will strengthen or dissipate going forward.

5. Changing Attitudes Toward Alcohol and Health

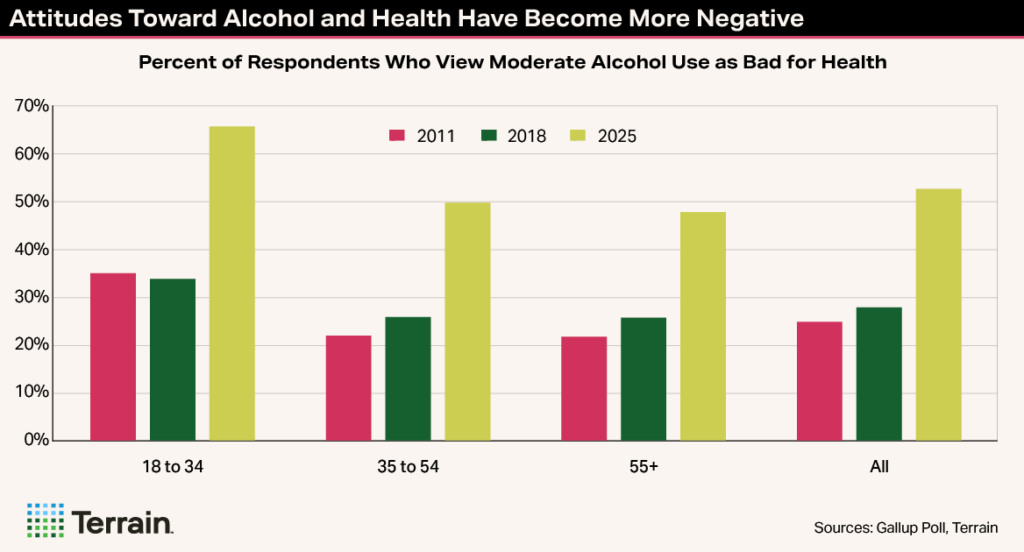

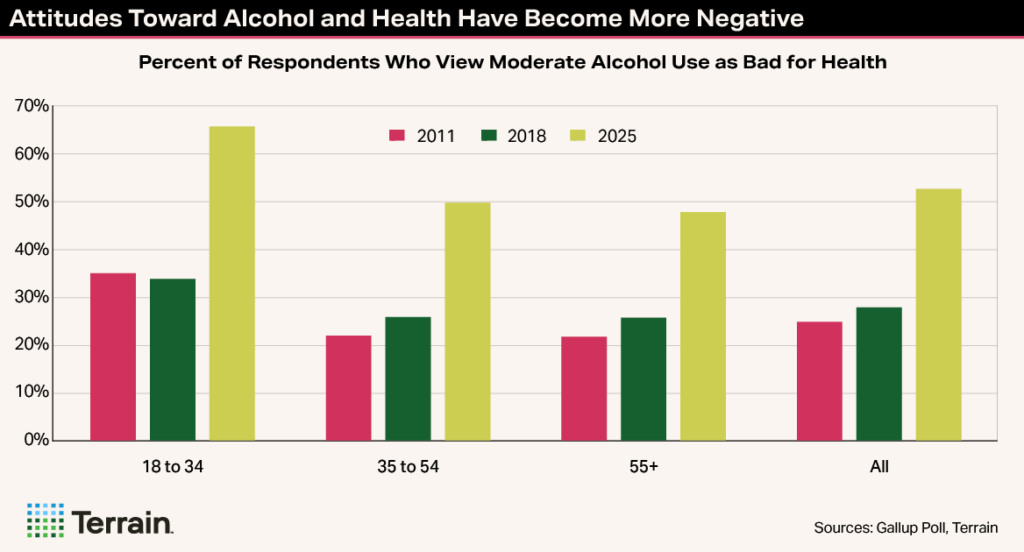

The Gallup poll periodically asks a question relating to alcohol and health. In 2018, 28% of respondents felt that moderate alcohol consumption was bad for their health. When the question was next asked five years later, the share had increased to 39% — and 53% concurred in 2025. Conversely, just 6% of respondents believed that alcohol was good for their health, down from a high of 25% in 2005.

While it is impossible to quantify, rising skepticism has almost certainly weighed on alcohol consumption in recent years.

While it is impossible to quantify, rising skepticism has almost certainly weighed on alcohol consumption in recent years. This is evidenced by the growing number of drinkers indicating they are “sober curious” or participating in events such as Dry January and Sober October. Moreover, the younger generations are most likely to subscribe to this view and their negativity will become more embedded going forward.

The opinion shift is partly the product of a burgeoning health and wellness movement that is evident in society more broadly. But a sophisticated and well-funded anti-alcohol movement, which has gained influence over the last decade, has surely accelerated the swing.

The anti-alcohol movement’s mission is clear: Reduce alcohol consumption by as much as possible. This is epitomized by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) widely broadcast statement in 2023 that “no level of alcohol consumption is safe.”

The anti-alcohol movement will continue to attempt to exert its influence on public opinion and policy going forward.

In one example, a federal organization dedicated to preventing underage drinking was tasked with providing a report to support revisions to the U.S. government dietary guidelines scheduled to be released later this year. The report from the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking has since been withdrawn by the Department of Health and Human Services, and inside sources now suggest that specific guidelines pertaining to alcohol use will not be included in the dietary guidelines.

In addition, the outgoing surgeon general has publicly advocated for cancer labels on alcohol products, though the Trump administration has not shown interest in pursuing this. WHO is also advocating for an increase in alcohol taxes worldwide to inhibit drinking.

Thus, the health issue is likely to continue to weigh on alcohol consumption.

Nonetheless, attitudes toward alcohol and health can be fickle, so it is not a foregone conclusion that they will become more negative. For example, there was a positive turn in the early 1990s after the “French Paradox” aired on “60 Minutes.”

The science is also far from settled. A recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine — also commissioned in conjunction with the dietary guidelines — found that moderate alcohol consumption was associated with lower “all-cause mortality.” In other words, people who drink in moderation live longer than those who don’t drink at all. So, it is not inconceivable that a more favorable view could emerge in time.

A Tenuous Outlook for Drinking

The recent decline in alcohol consumption does not just look to be a post-pandemic hangover. Economic pressures don’t appear to be the main cause either.

I don’t believe the moderation movement is a temporary phenomenon, and I expect alcohol consumption to continue to decline for the foreseeable future.

Thus, structural factors appear to be playing a key role, though it is impossible to disentangle their individual impacts. None are likely to dissipate anytime soon, and some are apt to stiffen. Several of these trends are also more pronounced in the younger generations and will become more deeply embedded in society with time. For these reasons, I don’t believe the moderation movement is a temporary phenomenon, and I expect alcohol consumption to continue to decline for the foreseeable future.

But it is also important to keep the situation in perspective. Alcohol has played an important role in society for many millennia, and there have been ups and downs before. Its role will almost certainly continue, though it may be diminished.

Because the drivers of the moderation movement are varied and difficult to quantify individually, it is impossible to predict the future trajectory of alcohol consumption with any degree of certainty. Even so, the past drinking recession can provide a relevant, albeit imperfect, guidepost. As Mark Twain opined, “History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

Following a period of steady growth during the supercharged 1970s, per capita alcohol consumption fell steadily between 1980 and 1995, with a total decline of 25%, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Like today, health concerns were at the forefront, though a backlash against drunk driving was also a hallmark of this period. This culminated in legal and regulatory changes, including an increase in the minimum drinking age to 21, lowered alcohol limits while driving in most states, and a requirement that alcohol labels include health warning statements.

While the causes of the current temperance movement are not identical, the headwinds seem at least as strong. However, there has been one crucial change since then: Population growth has slowed considerably.

The 25% decline in per capita consumption during the 15-year slump in the ’80s and ’90s resulted in a drop in total alcohol consumption of just 7.5%, or 0.5% per year, due to a surging legal drinking-age population. A similar percentage decline in per capita consumption between 2022 (when the current slump began) and 2037 would lead to a contraction of 17%, or 1.3% per year, because the adult population is projected to grow at less than half the rate, per Census Bureau projections.

Thus, the decline could be material and have far-reaching implications for the alcohol industry in general, and the wine industry specifically.

A Headwind for Wine, but Some Areas of Opportunity as Well

Wine is not immune from these headwinds. If alcohol consumption declines, the overarching implication is that wine will need to take market share at a similar rate just to maintain sales volume at its current level. This is a pressing challenge because wine has been losing market share since the late 2010s.

Declining alcohol consumption represents a serious challenge, but I believe that wine is well-positioned to attract consumers concerned with health and wellness.

The moderation movement also has repercussions for consumer behavior and preferences. Understanding these can help wineries and growers adapt to the evolving market environment and maximize their odds of success. I see three likely shifts, though there are surely more:

- Premiumization. If consumers drink less, they are apt to treat it like an indulgence and drink higher-quality beverages when they drink. Presumably, they will be able to spend more because they are purchasing fewer bottles. Thus, the moderation movement is likely to have less impact on the premium and luxury segments.

- Wine styles. If consumers are more concerned with health and wellness or taking GLP-1 drugs, lighter, crisper wines with less oak, alcohol and calories should become more appealing. Alcohol-removed wines should also continue to gain traction. This has implications for both wine making and grape growing practices.

- Packaging formats. If more consumers are drinking alone or less due to age, health concerns, or GLP-1 drugs, then the 750 ml bottle may not be suitable on as many occasions. Thus, there may be a shift in demand toward smaller formats (splits, cans, etc.) and containers that preserve freshness for longer like bag-in-box.

Declining alcohol consumption represents a serious challenge, but I believe that wine is well-positioned to attract consumers concerned with health and wellness because it has some distinct advantages over other alcoholic beverages.

Wine is inherently a natural product: It is simply fermented grapes and typically low in harmful additives. It contains no fat, and generally no added sugar, and dry wines are relatively low in carbs and calories. Organic and sustainable options are widely available.

Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that wine has potential health benefits not found in other alcoholic beverages. For example, the antioxidants from grape skins are thought to promote heart health when wine (particularly red wine) is consumed in moderation.

The industry must strive to tell the story of wine in a simpler and more compelling manner.

And more so than any other alcoholic beverage, wine is not just a means to a buzz. It is meant to be savored and shared with friends and family. It is sophisticated. It enhances the enjoyment of meals. It is steeped in history, culture and geography. In essence, it is the drink of moderation.

These virtues should appeal to consumers of all ages and the younger generations in particular, though they may not yet realize it. The industry must strive to tell the story of wine in a simpler and more compelling manner.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.