The crush was below average for a third consecutive year and the smallest since 2011

According to the National Agricultural Statistical Service’s preliminary California Grape Crush Report, the 2022 crush came in at 3.35 million tons, down 8% from 2021 and 13% below the ten-year average. It was the smallest crush since 2011. Red tonnage was off by 12% versus the average, while white tonnage was short by 14%.

Following a seven-year period of relatively stable and generously sized harvests, fires, drought and other severe weather events have taken a toll on the California grape crop over the past three years. The 2022 crush was the smallest in the past 10 years, while the 2020 and 2021 crushes were the second and third lightest, respectively. The crush has averaged just under 3.5 million tons over the last three years – which compares to an average of more than four million for the prior three – a deficit of 15%.

All down, but variability across regions

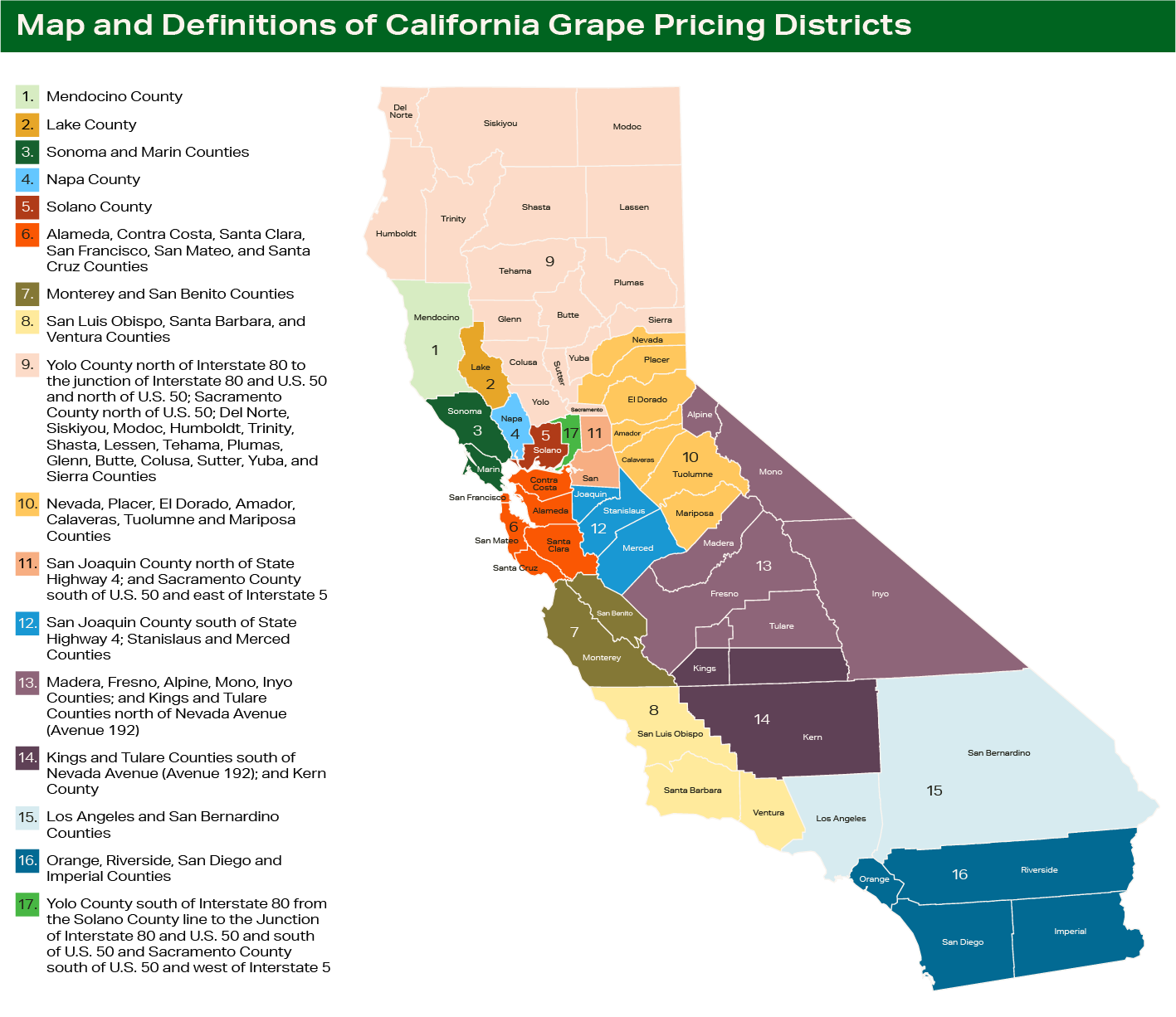

Output was well below average in both the coastal and interior regions of the state in 2022 though the North Coast fared better than the Central Coast and the Northern Interior was closer to the average than the Southern Interior, where some vineyards have been pulled in recent years.

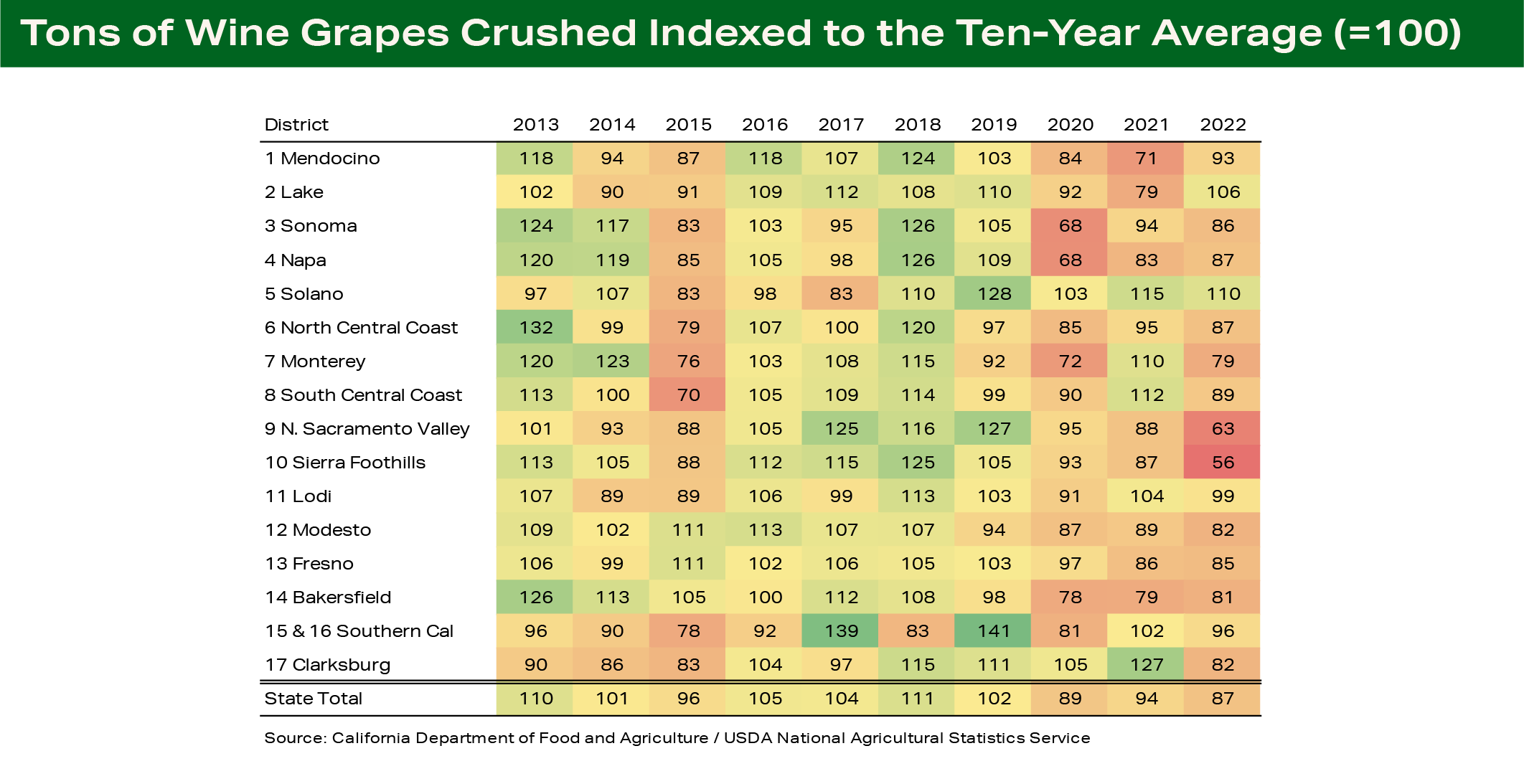

Figure 1 depicts the size of the crush in each district indexed to its ten-year average, which is assigned a value of 100. Values greater than 100 indicate a larger than average crush, while those fewer than 100 signify a smaller than average crush in that year.

Some highlights of note:

Prices were up in nearly all districts in 2022 – but the market remains bifurcated

The average price paid for a ton of California wine grapes rose by 5% in 2022 to $944. Red grape prices jumped 7%, while white varietal prices rose just 1%. The smaller increase for whites, though, was partly attributable to a redistribution of sales from the coast to the interior.

Pricing was up across the state in 2022. The average price per ton rose in 15 of 17 districts. Prices increased by 5% or more in six of the eight coastal districts, led by a 12% gain in Napa. All five of the interior districts recorded higher prices and appreciation improved progressively moving north to south.

Year-over-year fluctuations in average grape prices can be influenced by shifts in the mix of grapes sold and tend to be a lagging indicator of changes in the market because many sales reflect prices paid based on contracts signed in prior years. Thus, annual changes are best viewed as a directional indicator.

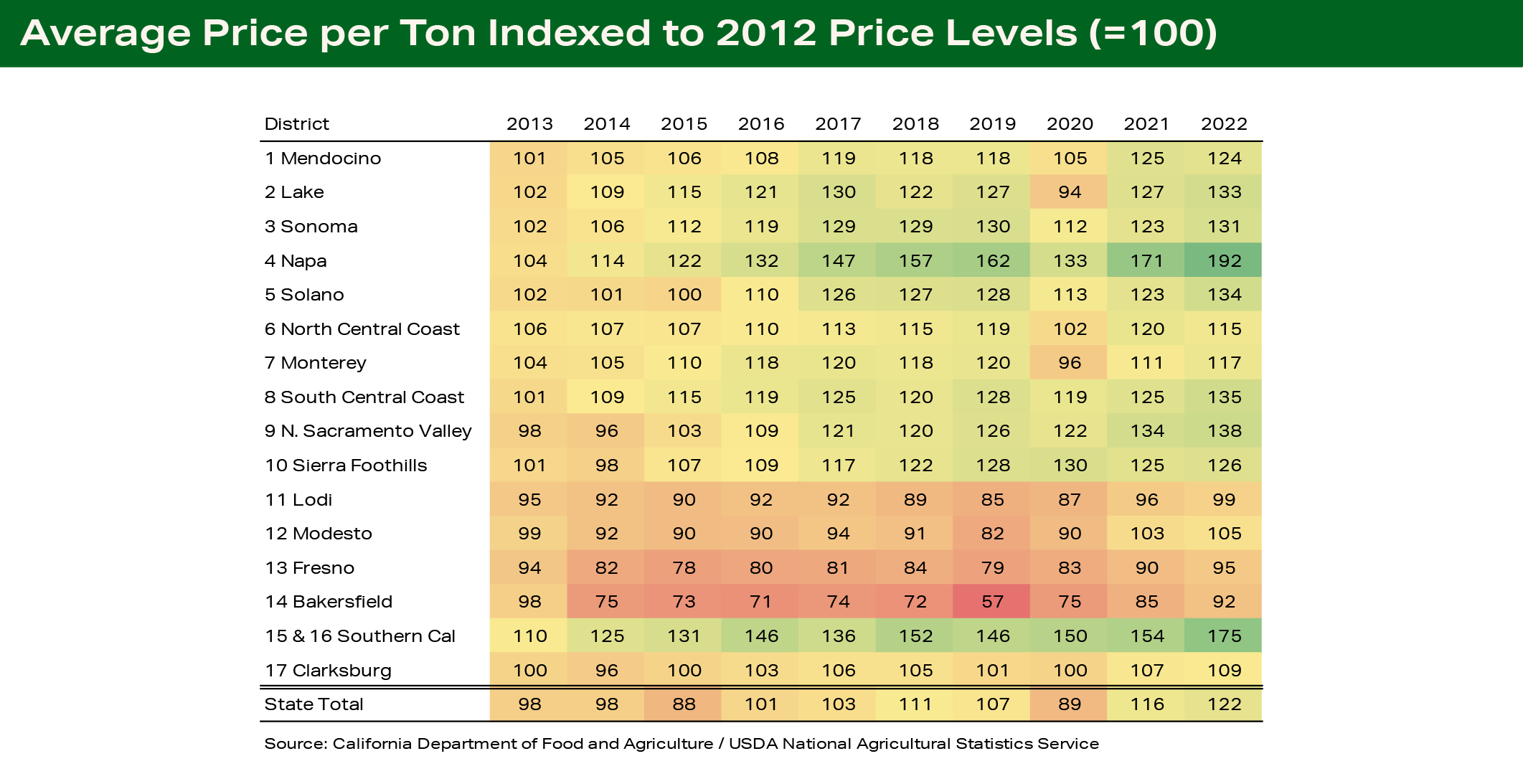

Viewing prices in a longer-term context provides additional insight into the state of the grape market. In Figure 2, the average price in each district is indexed to its level from ten years ago, which is scaled to 100. The chart indicates that the trajectory of prices has varied markedly between the coast and interior, and the higher-priced districts in each region have generally had more appreciation than the least expensive districts.

Grape prices in the interior declined steadily between 2012 and 2019 as shrinking demand for value priced wine, which is primarily sourced from interior grapes, led to oversupply. Prices have rebounded in recent years as supply has been pared back, but there has been little or no appreciation over the past decade. Average prices in the two largest interior districts (11 and 13), which account for more than half of California’s grape output, remain below their level in 2012.

Conversely, the coastal regions have recorded solid appreciation over the past ten years, interrupted only by the pandemic and smoke-impacted 2020 vintage. This mirrors growing demand for premium wines, which are typically sourced from the coastal districts.

Market outlook: headwinds rising?

Grape prices depend on supply, demand and bottle prices. Recent price gains have been driven more by depressed supply than growth in consumer demand or rising wine prices, particularly at the value end of the market. Over the next year or two, we are likely to see more supply – and prospects for demand growth appear to be muted.

The demand side of the equation is unusually murky due to pandemic-related distortions in wine sales and an uncertain economic environment. Nonetheless, near-term headwinds are evident: consumers face a combination of inflationary pressures, rising interest rates, declining asset values and possibly a recession.

These headwinds could induce some trading down and potentially slow the long-standing decline in the value segment of the market, but it almost certainly won’t be enough to reverse it. And competition from imports is likely to heat up as supply chain disruptions ease and shipping costs abate.

It is true that higher-income consumers (particularly those at the very top) are insulated from these pressures to some extent – but they are not immune – and may become less willing to splurge if their assets continue to shrink. Nielsen data is signaling already that growth in premium and higher-tier wine sales is beginning to fade.

Finished wine prices also impact wine producers’ willingness and ability to pay for grapes. Suppliers to all segments of the market are finding it challenging to raise prices without sacrificing volume, and margins are being squeezed. Thus, they will resist paying higher prices for grapes unless tight supply forces them to.

On the supply side, recent winter storms have gone a long way toward alleviating the severe drought conditions that have depressed grape yields in many parts of California. This sets the stage for potentially larger crops over the next several years, assuming the weather cooperates. And while some interior vineyards have been pulled out, these removals have been offset to some extent by the addition of bearing acreage in other parts of the state.

So, four million tons may still be the mark under “normal” weather conditions, with perhaps a slightly lower ceiling in the interior than in the past, and a slightly higher ceiling in the coastal regions.

As discussed earlier, grape output has averaged just 3.5 million tons over the past three years. Even so, there has been relatively little drawdown in wine inventories, which still appear to be in line with consumer demand overall. As always, certain varietals from certain appellations are in short supply while others are long.

Thus, a rebound in grape production to its long-term average of four million tons could tip the balance toward oversupply – unless there is an upside surprise in wine sales. Excess supply, if it materializes, will inevitably depress prices, or at a minimum, flatten appreciation rates in affected market segments.

Given the prospect of softening market conditions, maintaining realistic expectations will be important for growers. It will also pay to closely monitor wine sales trends in order to make informed decisions regarding planting, removals and grape contracts.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.