All Eyes on Milk Surplus in 2026 as Prices Slump

Article Originally Published in the January 25, 2026, Issue of Hoard’s Dairyman

Report Snapshot

Situation

Milk production has been growing dramatically in the U.S. as well as abroad in the EU and New Zealand. When the world is awash in milk, lower prices are hard to avoid. The all-milk price in October was reported at $20, down more than 20% from last October.

Outlook

There’s reason to hope that milk prices will improve in the next few months, but it will depend on how quickly the market can resolve a surplus of milk.

Finding

Low milk prices will be painful in the near term, but they could set the stage for a more balanced market later in 2026.

Milk Prices Enter 2026 on a Low Note

Milk prices began falling at the end of 2025 and are set to start 2026 at a much lower level. Will this be the beginning of a drawn-out lull in prices, or will low prices be the cure for low prices and lead to a rebound later in the year?

There’s reason to hope that milk prices will improve in the next few months, but it will depend on how quickly the market can resolve a surplus of milk.

Dealing With Surplus

Milk production has been growing dramatically in the U.S. (up 4.5% year over year in November and above 3% each month since June) as well as abroad in the EU and New Zealand. When the world is awash in milk, lower prices are hard to avoid.

For years, U.S. milk supply was steady, with flat year-over-year volumes. Meanwhile, components continued to climb within that same volume of milk. Now both milk volume and components are rising because of a milk cow herd that’s the biggest in decades. And today’s cows are yielding much higher milk output with record levels of components in that milk.

Exports usually help absorb extra milk supply in the U.S., and they have been strong, especially for cheese and butter. But when the EU boosted milk production, global competition intensified. In commodity markets, competition can result in a race to the bottom on price. U.S. products are still moving overseas, but at much lower prices.

Butter Fell First, Then Cheese

Butter markets fell first. In my previous contribution to this column in April, I suggested that fat could come under pressure later in the year because of surplus cream on the market. After some hopeful signs that I might be wrong in late spring, the spot price of butter fell from $2.60/lb. at the beginning of July to around $2/lb. by early September and $1.40/lb. by the end of the year.

The price of cheese followed. After bouncing within a range of $1.60 to $1.90 since late 2024, the spot price for block cheddar cheese ended 2025 near $1.35.

The cause was similar in both cases. There was ample supply of butter because churns were full of oversupplied cheap cream. There was plenty of cheese because of expanded manufacturing capacity and a growing supply of milk. Both were supported as long as exports could remain strong. But once global prices fell (first for butter and later for cheese), the U.S. price needed to fall to keep product moving overseas.

Nonfat dry milk has given up some of its gains earlier in the year, but to a less dramatic degree than cheese or butter. Whey, meanwhile, has been the bright spot given strong domestic demand for protein. Still, putting this all together, the impact on milk prices is decidedly negative. The all-milk price in October was reported at $20, down more than 20% from last October. That’s despite the fat content being 2% higher this year.

Will Low Prices Cure Low Prices?

Traditionally, falling prices squeeze margins until production slows. This time, the adjustment may take longer for two reasons:

- Beef revenue cushion: I calculate dairy-beef cross calves and elevated cull values add $3/cwt to $4/cwt in milk-equivalent income for many producers.

- Risk management coverage: Some producers locked in favorable margins for late 2025 and early 2026 through Dairy Revenue Protection or other hedging tools, muting market signals.

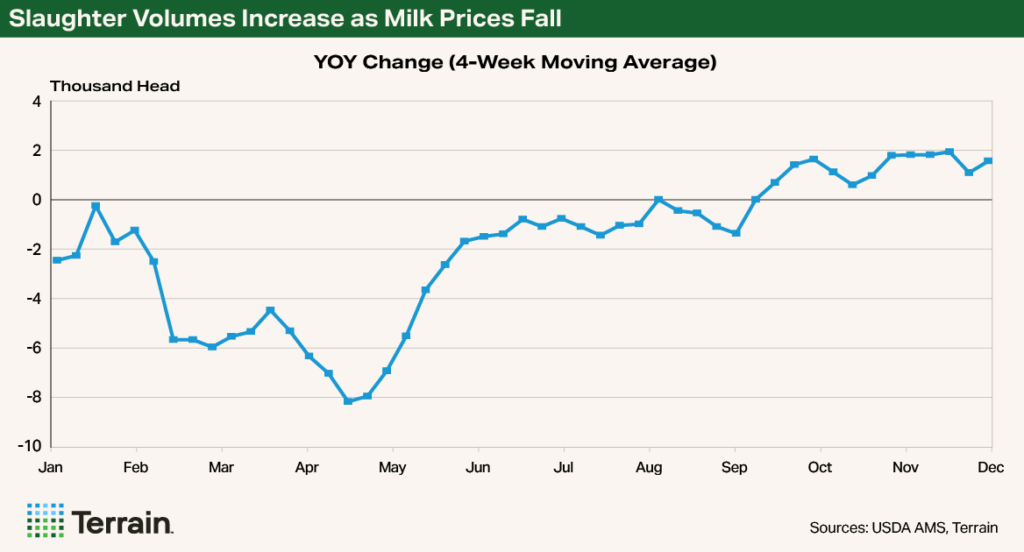

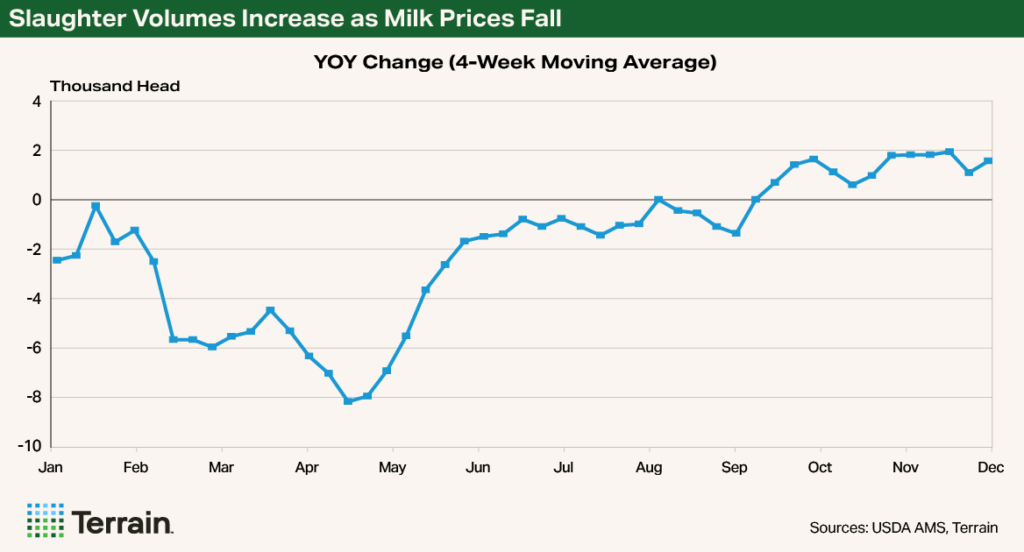

Still, a 20% price drop is hard to ignore. Slaughter volumes are already trending higher, up 3% year over year on a weekly basis since September, signaling that producers are responding.

To the extent that we do see some contraction in the milk cow herd, rebuilding won’t be quick. The U.S. herd has skewed older, with cows sticking around for an additional lactation, and the supply of replacement heifers is still tight. So, a sudden contraction could take some time to rebuild, which would be positive for prices.

The previous peak in cow numbers in recent history was in May 2021 at 9.509 million head. By January 2022, the herd was 141,000 head smaller. It took more than four years and some elevated prices to get back to that previous high.

Looking Ahead

Even if supply tightens, global prices will continue to influence U.S. markets. Domestic demand offers some upside longer term, but dairy consumption is sensitive to economic conditions. Rising unemployment could weigh on food service sales — a key channel for dairy.

Low milk prices will be painful in the near term, but they could set the stage for a more balanced market later in 2026. How that plays out will depend on how quickly production responds, how global markets perform, and how resilient domestic demand proves to be.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.