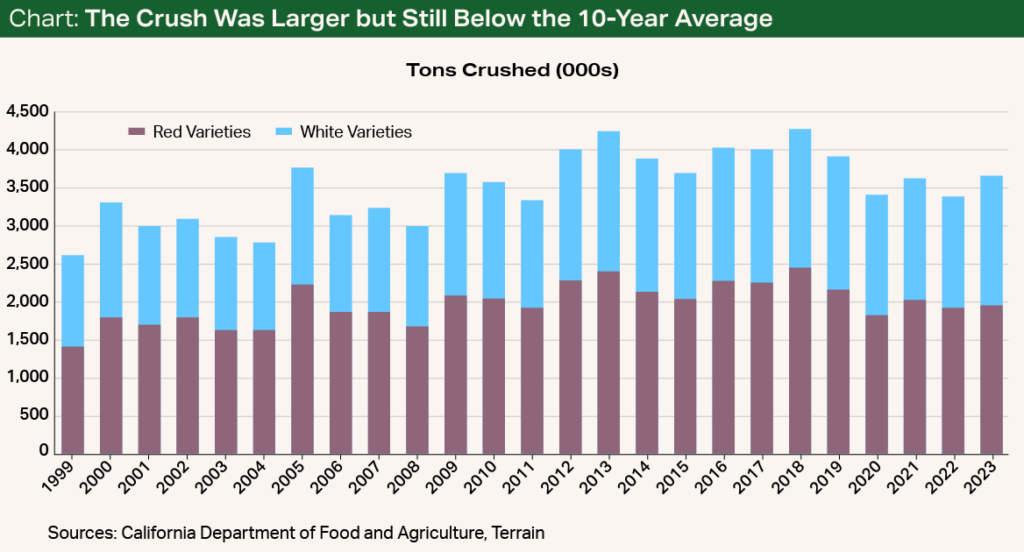

The California Department of Food and Agriculture’s preliminary California Grape Crush Report recorded the 2023 crush at just under 3.7 million tons, the largest total since 2019. Nonetheless, it was still a below-average crush by historical standards. Indeed, fewer tons were crushed in 2023 than in any year from 2012 to 2019 (see Chart).

Demand is no longer strong enough to absorb a crop that would have been considered to be in the “normal” range prior to 2020.

The crop itself was even larger, but a substantial amount of fruit was left on the vine because there was no buyer. The quantity of unpicked grapes is not tracked in the crush report, but market observers estimate that it was at least several hundred thousand tons. Had all grapes been utilized, the crush likely would have been in line with the 2012 to 2019 average.

This is an indication that demand is no longer strong enough to absorb a crop that would have been considered to be in the “normal” range prior to 2020. This isn’t surprising given the downward trend in California wine shipments in recent years. A post-harvest surge in bulk wine available for sale makes it clear that even the 3.7 million tons of grapes that were actually crushed more than met demand.

The Oversupply Issue Is Not New

In essence, the capacity to produce grapes under “normal” conditions exceeds what California wineries need to satisfy demand for California wine. Grape acreage has simply not yet adjusted to the reality of shrinking wine consumption.

The problem is not new. It was masked by short crops from 2020 to 2022 and a brief surge in wine sales during the pandemic. Despite the short crops, grape prices have fallen in real terms since 2019, which suggests the imbalance between supply and demand has been brewing for some time.

The oversupply issue is most acute in the interior. Interior grape prices have been stagnant for a decade in absolute terms and have fallen sharply in real terms because of inflation. Demand for interior grapes has weakened steadily because of declining case sales in the under-$11 segment of the wine market and stiff competition with imports.

The solution to the grape glut will almost certainly entail the removal of vines. The question is not if, but what and where.

The coastal region has fared better, as it has been more favorably positioned with respect to wine market trends, particularly premiumization. Nonetheless, grape prices in most coastal districts peaked in real terms in 2017 and have declined since then in every district except Napa. (For a more complete analysis of grape crush data across regions, read the latest “Winescape” report.)

To restore the balance between supply and demand, either wine shipments must improve or acreage must be removed. Given the muted outlook for wine sales in the near to medium term, the problem is not likely to be solved by an increase in demand alone. Another series of short crops could also correct the imbalance, at least temporarily, but this can’t be counted on. So, the solution to the grape glut will almost certainly entail the removal of vines. The question is not if, but what and where.

Weighing Options

Pulling vineyards is obviously a painful decision. Alternatives include waiting it out and doing as little farming as possible until a contract is landed, or replanting to new varieties in the hopes that demand will materialize by the time the fruit begins to bear. These decisions must be approached thoughtfully and on a case-by-case basis, as there are many considerations involved.

Waiting it out is not likely to be a good course of action for interior growers.

Waiting it out is not likely to be a good course of action for interior growers. Even under an optimistic scenario for the wine market overall, the under-$11 segment of the market is likely to continue to contract, and competition with imported bulk wine will be stiff. Given this, it may make sense to pull underperforming and older vineyards in marginal areas that need to be replanted immediately.

The calculus is less clear-cut on the coast and more specific to appellations and varieties. Prospects for the premium and luxury segments of the wine market look better, but even if growth resumes, it is likely to be more modest than it was prior to the pandemic. In addition, bearing acreage will continue to increase over the next several years if no vines are pulled. Removing uncontracted vineyards near the end of their economic life may be warranted on the coast as well, as replanting will be difficult to justify given the high costs involved.

It will likely be some time before enough acreage is removed to stimulate growth in grape prices.

The realization that vineyards need to be pulled has begun to take root. But it will likely be some time before enough acreage is removed to stimulate growth in grape prices because there are few if any viable alternative uses in most areas at this point.

The industry will eventually work its way out of the grape glut, as it has always done. In the meantime, growers should continue to focus on improving operational efficiency in order to maintain profitability.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.