Outlook • April 2023

Population or Prosperity?

Implications of China’s Population Decline for American Agriculture

Report Snapshot

Situation

Demand from China has been a primary driver for agricultural markets in the 21st century. In 2022, China’s population declined. Many are concerned that this means that the agricultural boom is coming to an end.

Finding

China’s food demand growth is driven more by income growth than by population growth.

Outlook

As long as growth remains strong for China and other middle-income nations, the rapid growth in agricultural commodity demand, particularly meat and animal feed, should remain intact.

Impact

U.S. commodity and land prices are not threatened by changes in China’s growth rate.

On January 1, 2000, the price of corn in the U.S. stood at $2.01/bu., soybeans were at $4.56/bu., and oil sat at $27.21 per barrel. By the summer of 2008, those prices had pushed to $7.20/bu., $16.05/bu., and $140 per barrel, respectively. The dramatic rise in global demand had fundamentally changed the price level in commodity markets. While biofuels production was seen as the primary contributor to price increases, Chinese demand growth easily doubled the impact of American biofuels.[1] In the years since, Chinese demand for vegetable protein, primarily in the form of soybean and soymeal imports, and animal protein in the form of pork, have continued to drive agricultural markets.

In early 2023, China’s statistics agency announced that deaths in their country exceeded births in 2022. Many commentators questioned whether this heralded the end of an era of high growth and high profits for U.S. agriculture. After all, if the largest country in the world has a declining population, what might that mean for the agricultural economy? These concerns overlook the critical role that eating better plays as consumers become wealthier.

For agricultural demand, the most important characteristic of consumers in any nation in the world is not their population growth but their long-term income growth. For the nations who represent the recent past and near future of food demand growth, that income growth appears to remain intact.

Food Demand and Population Growth

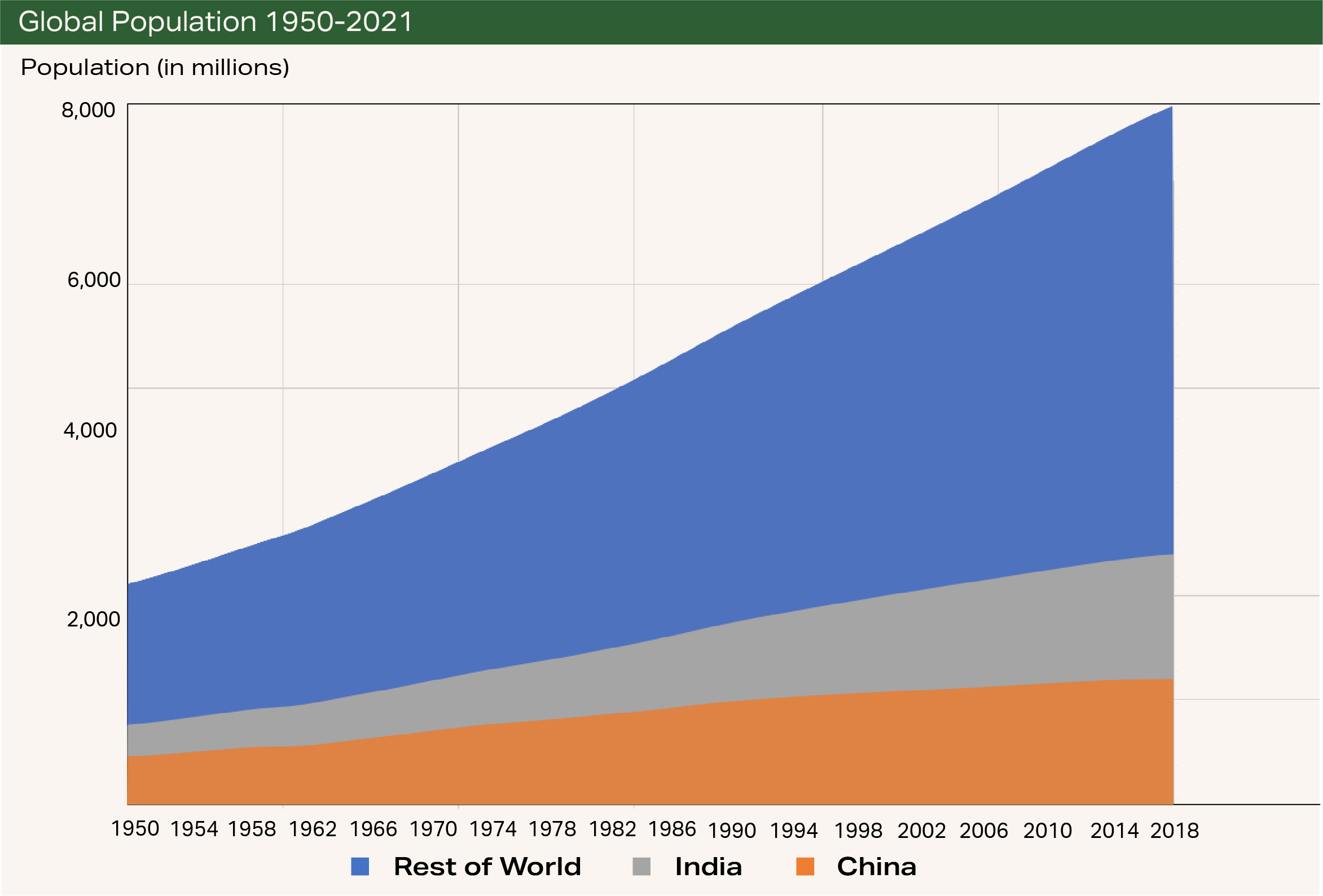

Since the end of World War II, the absence of major wars, increased prosperity, and improvements in medical care have resulted in world population climbing from 2.5 billion to nearly 8 billion people. The increase in population naturally has increased food demand. The green revolution provided a simultaneous boost in agricultural productivity that meant that even as population rapidly grew, the total amount of food available for consumption also grew.

Despite growth in demand from ever larger and wealthier populations and swings in supply from weather and political shocks, food prices remained relatively steady from 1950 through the 1970s, and then the 1970s through the early 2000s. Agricultural productivity was able to keep up with demand growth.

“Better” Food Demand and Income

In the U.S. and other wealthy nations, we have by and large long since crossed over to choosing food by quality instead of quantity, and the trajectory of nations who’ve transitioned from developing to developed countries over the past decades, such as Greece, Portugal, Japan, and South Korea, repeat this pattern.

In developing countries, more income means that consumers have a more complete and nutritious diet. These substitutions toward better diets don’t end when consumers rise out of poverty. Substitutions continue as consumers choose “better” foods—whether more flavorful, more nutritious, more exotic, or any of dozens of other potentially appealing characteristics.

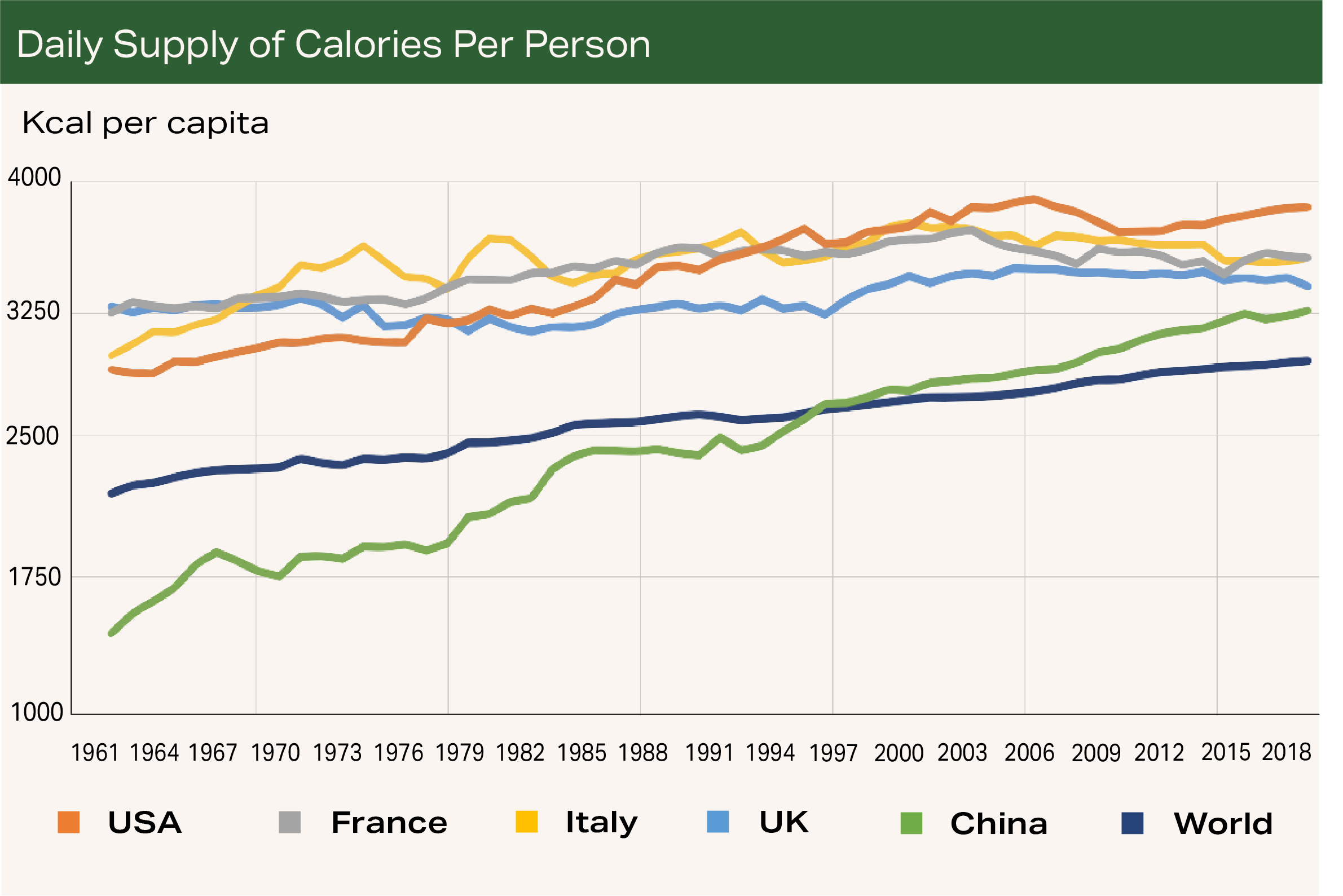

As income begins to rise out of poverty levels, the initial changes are to add more calories and nutrients to meet basic nutritional needs. These additional calories are often met through grains such as rice, wheat or corn, depending on culture and geography.

As incomes increase and basic caloric needs are met, the next steps are to introduce a more complete diet, adding vegetables to meet additional nutritional needs and/or legumes or animal fats and oils to complete the amino acid profile needed for muscle development.

At these still impoverished levels, additional income earned by the household is largely spent on purchases of additional foodstuffs, and those purchases result in the household consuming more food – more calories and nutrients. Factors such as taste and convenience are less consequential compared to affordability and availability.

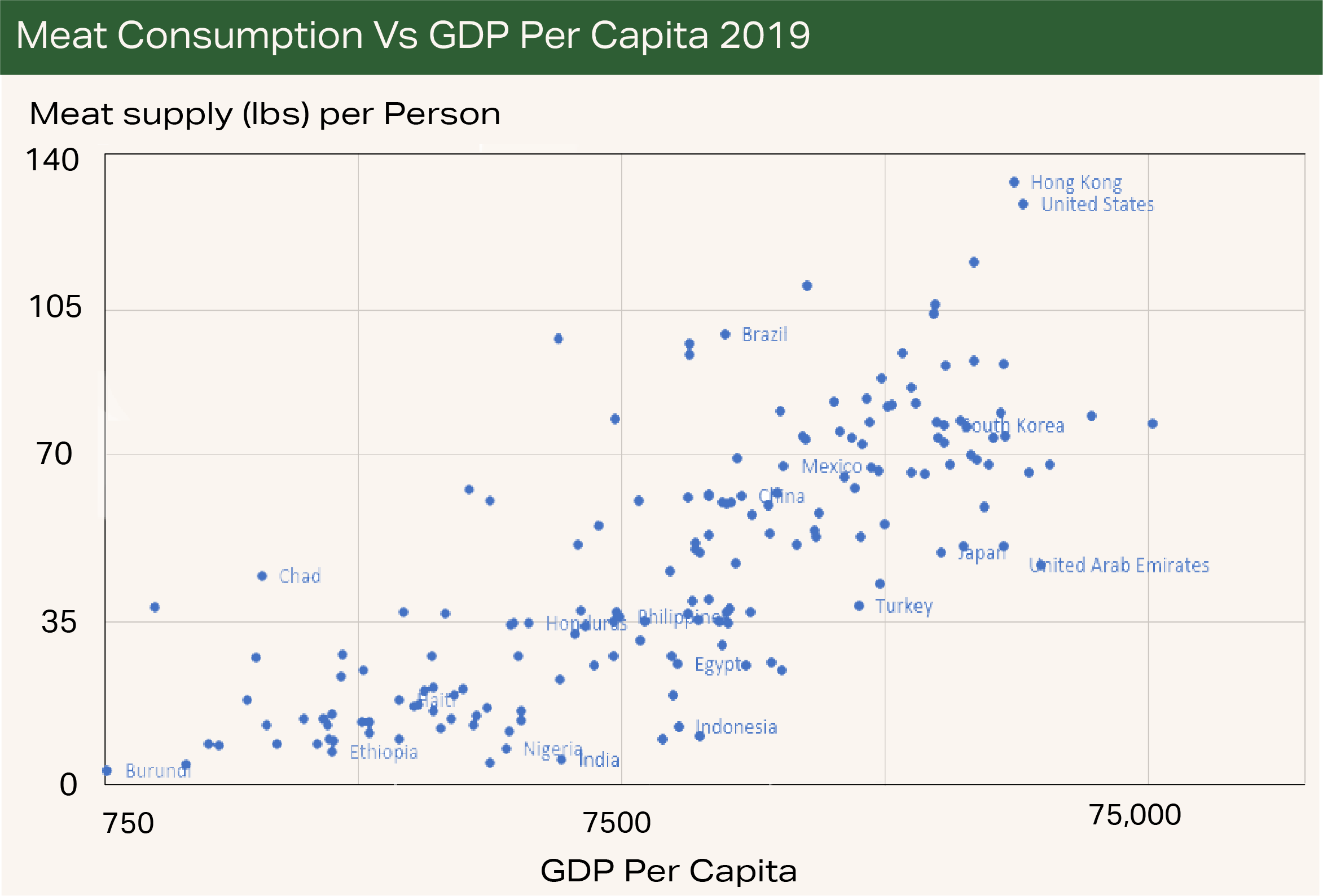

Even as consumers get closer to and move through middle-income bracket levels, their consumption of food continues to grow with income. They also consistently add more meat and/or fish to their diets. In fact, across all nations and income levels, I find that the income elasticity of demand for meat, i.e. the change in meat consumption when income changes, is 0.58. This means that for every 1% increase in income, meat quantity consumption increases by 0.58%.

This elasticity varies across countries; China’s is a bit lower, at 0.4%. Compared to their population growth rate since 1990, which averaged 0.72% per year, and is declining, their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth has averaged 8.50% per year, and their consumption of meat and fish has grown at an average annual pace of 3.97%. While the role of a growing population does increase demand for food, it is less important than the role of growing income for that population.

Adding Agricultural Value

Income growth not only drives an increase in volume demand. It also drives animal carcass values up and provides avenues for more specialty or branded production.

When it comes to meat, higher quality choices mean choosing more desirable meats and cuts – muscle cuts instead of organ meat, farmed beef instead of backyard poultry or scrap-fed pork. In this context, better also means a smaller and smaller portion of the animal is used or desired for food consumption. In the case of beef, steaks instead of roasts, or pork bellies instead of hocks. Therefore, increasing demand for higher quality foods, while holding population constant, has a similar effect on prices as increasing the overall population while holding per capita income constant.

The same dynamic also applies to crop output. “Better” foods are often more land- and resource-intensive than low-cost commodity outputs. Higher income, holding population constant, might reduce the demand for commodity foods, such as wheat or rice, while increasing the demand for vegetables, fruits, or specialty production, such as local or organic crops. In terms of the value of their agricultural and food consumption, China’s growing income will more than offset the impact of their declining population.

Bright, Long-Term Demand Outlook

Population growth is the secondary driver of demand for agricultural products. Rising standards of living are the main source of demand growth for China and other nations.

While China has experienced rapid economic growth in the past decades, it still has far to go. In 2020, China was still a middle-income country, with per capita GDP of $16,315, between Libya and Serbia, but still less than Mexico ($19,677) and Costa Rica ($20,937).

As long as China’s income growth remains intact, the future of U.S. agriculture remains bright.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.